Imagine an elder sign or portal stone kepted unknown in someones garden until the stars are right.

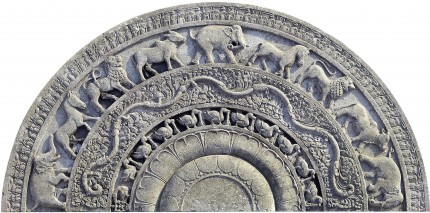

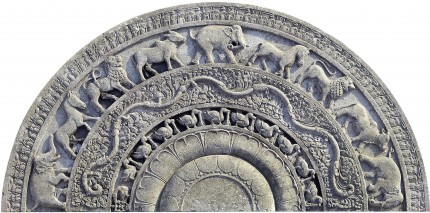

A Sandakada pahana, a beautifully carved semi-circular granite slab which a thousand years ago graced the entrance to a temple in Anuradhapura, a sacred Buddhist city and a capital of Sri Lanka from the 4th century B.C. to the 11th century A.D.,

has been found in the garden of a modest bungalow in Devon. Sam Tuke, an appraiser at Bonhams, happened to hear about it from a woman who was in the office picking up something else. When she mentioned the elaborate carvings of animals which she had loved tracing with her fingers since she was a small child, the expert was intrigued. The client brought him a picture of it the next day and he realized it was something special.

It is so special, in fact, that it’s one of only seven of its kind. The other six are all still the first steps to stupas (spired dome temples representing the enlightened mind of the Buddha) in Anuradhapura. The tradition of the elaborately carved first step goes all the way to the dawn of Buddhism. According to tradition, the practice began in India when the Buddha was still alive. A devotee had covered the floors of the temple he had built with expensive, richly patterned cloths. When another devotee wanted to do the same, Ananda, the Buddha’s personal attendant and first cousin, suggested she place them at the base of the temple steps. From then on, the first step would be a beautiful art work.

In Anuradhapura, this tradition took the form of carved stones. Sandakada pahana means half-moon stone in the Sinhala language and indeed all the steps are semi-circular in shape. The designs carved within the half-moon are laden in Buddhist symbolism, representing the life of the Buddha and the cycle of Samsara (birth, life, death and reincarnation). Within the half-moon are concentric half-circles carved with Buddhist symbols. In the center is a half lotus in bloom. The lotus represents purity of spirit as it floats unblemished above the mud of earthly attachment. When the Buddha was born, he took seven steps and at each step a lotus flower blossomed.

The next band is a line of geese (some call them swans, but swans aren’t native to the region and the creatures don’t have long necks). Geese are considered examples of ideal qualities — they aren’t vainly adorned like peacocks but they can fly to much greater heights, their migration shows a lack of attachment to home, they make pleasing sounds — and the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra tells the tale of a young Prince Siddhartha saving a goose which had been shot with an arrow by his cousin and nursing it back to health.

After the geese is a band of foliage called a liyavel, a stylized design symbolizing worldly desires, and after that is a parade of four animals: elephant, horse, lion and bull. They follow each other in that order representing the four phases of Buddha’s life.

The elephant represents the Buddha’s birth and growth. One night before he was a twinkle in her eye, his mother Queen Maya dreamed that a white elephant holding a lotus flower in its trunk walked around her three times then entered her womb. The white elephant, symbol of mental strength greatness, was the Buddha himself returning to life in his final incarnation as Prince Siddhartha. The horse represents energy and effort in the practice of dharma. Buddha rode his horse, Kanthaka, when he left the palace for good to live as an ascetic begging for alms. The lion symbolizes power and the teachings of the mature Buddha which are also known as “the Lion’s Roar.” The bull represents forbearance and the acceptance of death. An alternate interpretation of the four animals is that they represent the four mortal perils: birth (elephant), disease (lion), decay (bull) and death (horse).

The outermost band is a carving of stylized flames representing the fire of worldly existence.

The Sandakada pahanas were created towards the end of the Anuradhapura Kingdom. Sri Lanka was invaded by the Tamil Chola Empire of India in 993. Anuradhapura king Mahinda V, a weak ruler who made the fatal mistake of not paying his army, was finally captured in 1017. He was kept prisoner in India while the Chola army sacked the sacred city of Anuradhapura. They then moved the capital of Sri Lanka to Polonnaruwa tolling the final death knell of the Anuradhapura Kingdom. The city was abandoned and the jungle reclaimed the ruins.

It wasn’t forgotten, however. It had been written about extensively by ancient Roman (Pliny the Elder in

Book VI, Chapter 24 of Natural History refers to the travelogue of Annius Plocamus whose servant was blown off course to Sri Lanka) and Chinese sources. In the 1820s and 30s, British colonial administrator Sir William Colebrooke describes the art and architecture of Anuradhapura, and a Sandakada pahana in particular, in glowing if Eurocentric terms.

“I saw here ornamented capitals and balustrades, and bas reliefs of animals and foliage. I cannot better express my opinion of their elegance than by saying that, had I seen them in a museum, I should, without hesitation, have pronounced them to be Grecian or of Grecian descent. One semicircular slab, at the foot of a staircase, is carved in a pattern of foliage which I have repeatedly seen in works of Greek and Roman origin.”

So how did this masterpiece of immense cultural importance find its way to a Devon bungalow? It was in the garden of the current owner’s childhood home in Sussex. Her parents had purchased the house from a tea planter in the 1950s, a tea planter would certainly have good reason to visit Sri Lanka, or Ceylon as it was then called, and in those days could easily have purchased some loot from Anuradhapura and brought it home.

When her parents died, the Sussex house was sold, but the owner of the stone couldn’t bear to leave behind a piece that had given her so much delight in the happy days of her youth. She took it with her. “The Pebble,” as the three-quarter ton, eight-foot by four-foot, six-inch-thick granite slab is known in the family, has moved with her five times since then. Now she’s parting with it for good, sadly. It will be sold at Bonham’s Indian and Islamic sale in London on April 23rd. They expect it will sell for at least £30,000 ($48,000), which seems very low to me considering its beauty and incalculable historic and cultural value.

I wish she’d donate it to a museum. It’s in such impeccable condition, which makes it even rarer than the six which remain in place since they’ve been stepped on by so many thousands of pilgrims and tourists.

It is so special, in fact, that it’s one of only seven of its kind. The other six are all still the first steps to stupas (spired dome temples representing the enlightened mind of the Buddha) in Anuradhapura. The tradition of the elaborately carved first step goes all the way to the dawn of Buddhism. According to tradition, the practice began in India when the Buddha was still alive. A devotee had covered the floors of the temple he had built with expensive, richly patterned cloths. When another devotee wanted to do the same, Ananda, the Buddha’s personal attendant and first cousin, suggested she place them at the base of the temple steps. From then on, the first step would be a beautiful art work.

It is so special, in fact, that it’s one of only seven of its kind. The other six are all still the first steps to stupas (spired dome temples representing the enlightened mind of the Buddha) in Anuradhapura. The tradition of the elaborately carved first step goes all the way to the dawn of Buddhism. According to tradition, the practice began in India when the Buddha was still alive. A devotee had covered the floors of the temple he had built with expensive, richly patterned cloths. When another devotee wanted to do the same, Ananda, the Buddha’s personal attendant and first cousin, suggested she place them at the base of the temple steps. From then on, the first step would be a beautiful art work.  It wasn’t forgotten, however. It had been written about extensively by ancient Roman (Pliny the Elder in Book VI, Chapter 24 of Natural History refers to the travelogue of Annius Plocamus whose servant was blown off course to Sri Lanka) and Chinese sources. In the 1820s and 30s, British colonial administrator Sir William Colebrooke describes the art and architecture of Anuradhapura, and a Sandakada pahana in particular, in glowing if Eurocentric terms.

It wasn’t forgotten, however. It had been written about extensively by ancient Roman (Pliny the Elder in Book VI, Chapter 24 of Natural History refers to the travelogue of Annius Plocamus whose servant was blown off course to Sri Lanka) and Chinese sources. In the 1820s and 30s, British colonial administrator Sir William Colebrooke describes the art and architecture of Anuradhapura, and a Sandakada pahana in particular, in glowing if Eurocentric terms.