Choose the design that best suits you the best. A few years ago, finding anything about trebuchets was pretty difficult, but these days there are many websites and several books that offer detailed building plans.

Draft the trebuchet's front, side and top view. The drawing must be to scale. This way you will have a clear idea what the finished project will look like and how much space it will occupy.

Draft plans for each of the trebuchet's components. A trebuchet consists of six basic components: base frame, upright supports, runway, swinging arm, counterweight bucket and sling.

Building the Base Frame

Put on your safety goggles. Cut three four-by-fours to a length of 4 feet on your table saw. Put the leftover 2-foot pieces to the side. One of the four-foot pieces is the base frame's front, another its back and the last one its central parallel brace.

Cut the leftover 2-foot pieces into four 1-foot long pieces on the table saw. Cut one four-by-four into two 4 foot long pieces. Place one of them to the side. Cut the remaining one into four 1 foot long pieces. You now have eight 1 foot long sections of four-by-four. Set the table saw's frame to a 45 degree angle. Cut off both corners of each 1-foot piece so that you have eight trapezoids with a 1 foot long base. These are the base frame's corner support braces.

Return the table saw's frame to the original setting. Set the blade's height to 1 3/4 inches. That's half a four-by-four's width. Cut the 4 foot long pieces at 3 1/2 inches and 44 1/2 inches. The frame will be put together with lap joints, so you're not cutting all the way through the lumber. Make four cuts into the 6-foot lengths: at 3 1/2 inches, at 34 1/4 inches, at 37 3/4 inches and at 68 1/2 inches. Make three additional cuts at equal intervals between the two cuts in the center. Punch out those central sections with the wood chisel and mallet.

Set the band saw's fence to 1 3/4 inches. Cut the ends of the 4-foot and 6-foot lengths so that each lumber's end has an L-shaped section cut out. All L-shapes must be on the same side.

Place the base frame's sides on top of the front and back end pieces and the central parallel support. Attach a Phillips head drill bit to your power drill and secure each joint with four 3-inch deck screws. Position the diagonal braces at the base frame's corners and to each side of the central parallel support. Secure each diagonal brace with 3-inch deck screws.

Building the Runway

Set the table saw's fence to 4 inches. On the table saw, cut one of the dimensional lumbers lengthwise. These two sheets are the runway's sides.

Make pencil marks on the base frame's front, back and central parallel support at exactly 20 inches and 28 inches. Align the 8 inch wide dimensional lumber with the pencil marks. Make sure it is precisely parallel with the base frame's sides. This is crucial to the finished trebuchet's accuracy. Secure it to the base frame with deck screws.

Cut six right-angled squares with 4 inch sides from your wood scraps. Secure these triangles with nails to the runway side pieces at 2 inches, 36 inches and 70 inches. Make sure that the right angles are all on the same side.

Place the runway side pieces against the 8 inch wide dimensional lumber. Fasten the triangular support brackets to the base frame with nails.

Buiding and Securing the Upright Supports

Cut six pieces of four-by-four to a length of 2, feet 9 inches on the table saw. Put two of these pieces to the side. These are the upright supports. The other for pieces are the support braces. Set the table saw's fence to a 135 degree angle. Cut the support braces along the top. Set the table saw's fence to a 64 degree angle. Cut the support braces along the bottom.

Draw a pencil line across the top of each upright support at 1 3/4 inches. Carry that line over to each of the support's sides. The line needs to drop down 1 3/4 inches. Mark the end of each line with an "X". Attach a drill bit to your power drill. Drill straight through the lumber, making sure you drill through the center of each "X." Attack the keyhole bit to the drill. Using the hole you just drilled as a pilot, drill as deeply into the wood as you can from both sides. You won't be able to cut entirely through the lumber. Punch out the center with the mallet. Remove all splinters with the wood rasps.

Make a pencil line across the upright support's top portion at 1 3/4 inches. That's halfway across the circle you just punched out. Cut off the top section on the band saw along this line.

Making the Axle and Swinging Arm

Draw an "X" across each end of your 4-foot four-by-four. With the compass, draw a 1 1/4 inch circle at the center of each "X." Draw a pencil line 3 1/2 inches from each end across all four sides of the lumber. Cut an octagonal shape around each circle's perimeter to the 3 1/2 inch line. Punch out the pieces around the octagon with the chisel and mallet. Round off the edges with the wood rasps so that you have perfect 3 1/2 inch cylinders on each end.

Set the table saw's blade to a height of 1 3/4 inches. Make cuts at 21 1/4 inches and 23 3/4 inches. Make three additional cuts at equal intervals between these cuts. Punch out the center sections with the chisel and mallet.

Cut a four-by-four to a length of 5 1/2 feet on the table saw. Set the table saw's blade to a height of 1 3/4 inches. Make a cut at 27 inches from the swinging arms front end and another at 30 1/2 inches. Make three additional cuts at equal intervals between these t two cuts. Punch out the center sections with the chisel and mallet.

Cut a 1 inch wide, 1 inch deep mortise into the swinging arm's back. Make the cuts on the band saw. Punch out the center with the chisel and mallet. The mortise must be vertical, not horizontal. Drill a hole through the swinging arm 1/2 inch from the top and 1/2 inch from the back, so that it punches through the entire mortise. Fasten a 3/4 inch eye hook to the top of the swinging arm, 1 inch below the mortise.

Building the Counterweight Bucket and Attaching the Aiming Pin

Place the 3 1/2 inch wide dimensional lumber on the table saw. Cut two 1-foot lengths, one 1 1/2-foot length and two 7 3/4 inch lengths. Cut the plywood to two rectangles, 1 foot x 1 1/2 feet.

Center one of the 1 1/2 foot long dimensional lumbers on the swinging arm's front end. Secure it with three 3 inch deck screws. This is the bottom of the counterweight bucket. The plywood rectangles are its sides. Secure them to the swinging arm and bottom with 3 inch deck screws at 2 inch intervals. Secure the 1 foot long lumbers to the bucket's front and back in the same manner.

Attach the 1 inch keyhole bit to the drill. Drill out a 1 inch wheel from the 1 inch thick dimensional lumber. Attach a 1/2 inch drill bit to the drill. Drill a 1/2 inch deep hole onto the wheel's side. Place the dowel into the hole and secure it with wood glue.

Place the wheel into the mortise at the end of the swinging arm so that the dowel points up. Secure it with a 4 inch bolt, two washers and a nut.

Final Assembly

Cut two 4 1/2 foot lengths of nylon rope. Cut an 16 inch long, 6 inch wide diamond from the denim cloth. Tie the diamond's front corner to one length of rope, the back corner to the other. Secure one nylon rope to the swinging arm's eye hook. You now have one free end of nylon rope. Tie this end into a 1 inch hoop. This hoop will hook onto the aiming pin when the trebuchet it loaded and ready to fire.

Place the axle onto the upright supports. Replace the upright support tops and fasten them with straight brackets and 1/2 inch wood screws. Make sure the axle can move freely before tightening the screws. Hang the swinging on the axle, mortise to mortise. Drill four holes through the mortise joint. Fasten the swinging arm to the axle with four 4 inch bolts, washers and nuts.

Fill the counterweight bucket with cat litter. Secure the two 7 1/4 inch pieces of dimensional lumber to the bucket's top with 3 inch deck screws.

Fasten a 3/4 inch eye hook to the top of the trebuchet's left runway rail, 6 inches from the trebuchet's rear. Cut a 6 foot length of nylon rope. Drill a hole into the center of each runway rail, 6 inches from the rear. This is the trebuchet's firing mechanism.

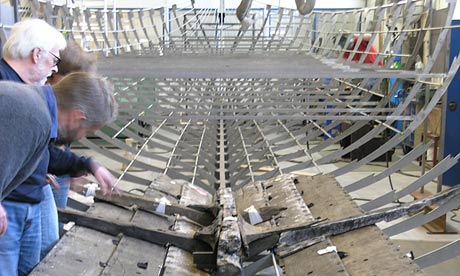

Good Luck - Result will look like the below photo