Byron’s copy of Frankenstein sells to UK collector

A first edition of Frankenstein sent to George Gordon, Lord Byron by Percy Bysshe Shelley and signed by Mary Shelley “To Lord Byron from the author” has sold to a private collector for an undisclosed sum. The good news is that the collector, who prefers to remain anonymous, will allow the book to go on public display in the UK. No exhibits have been organized as of yet, but I’ll keep you posted.

A first edition of Frankenstein sent to George Gordon, Lord Byron by Percy Bysshe Shelley and signed by Mary Shelley “To Lord Byron from the author” has sold to a private collector for an undisclosed sum. The good news is that the collector, who prefers to remain anonymous, will allow the book to go on public display in the UK. No exhibits have been organized as of yet, but I’ll keep you posted.Here’s a little something special about the find to tide you over as you wait. Peter Harrington, the rare book shop which sold the volume, had a private preview on September 25th which included a presentation about the writing of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley’s relationship with Lord Byron and the discovery of this signed copy. As I so often yearn for and so rarely find, they had the foresight and kindness to film the event and post a video of its highlights.

It starts with a brief introduction by Adam Douglas, Peter Harrington’s specialist in early books. This discovery is clearly the highlight of his career. “I’ve been a book seller for nearly 25 years now and I’ve been privileged to handle a number of exciting books, but I can honestly say that this copy of Frankenstein is the single most thrilling item that’s ever passed across my desk.” It didn’t occur to him or anyone else that this copy, which was known from a letter Percy Shelley wrote to Byron from Milan on April 30th, 1818, might have survived and be squirreled away in the library of a former Labour minister.

Enter the floppy-haired youth, Sammy Jay. In November 2011, Sammy was one of a phalanx of unemployed Oxford graduates with an English degree loitering around with nothing but time on his hands. His step-grandmother Mary, the second wife of his late grandfather Douglas Jay, generously put him to work sorting through his grandfather’s papers for the archives of Oxford University’s Bodleian Library. Among other roles, Douglas Jay was President of the Board of Trade (a committee of the Privy Council which is now part of the Department of Trade and Industry headed by a Secretary rather than a President) for three years (1964-67) under the Harold Wilson government. His papers would therefore be of interest to current and future historians of the period and were going to be kept in a proper archive at his alma mater.

Enter the floppy-haired youth, Sammy Jay. In November 2011, Sammy was one of a phalanx of unemployed Oxford graduates with an English degree loitering around with nothing but time on his hands. His step-grandmother Mary, the second wife of his late grandfather Douglas Jay, generously put him to work sorting through his grandfather’s papers for the archives of Oxford University’s Bodleian Library. Among other roles, Douglas Jay was President of the Board of Trade (a committee of the Privy Council which is now part of the Department of Trade and Industry headed by a Secretary rather than a President) for three years (1964-67) under the Harold Wilson government. His papers would therefore be of interest to current and future historians of the period and were going to be kept in a proper archive at his alma mater. Sammy says he almost missed the “little volume lying at an angle in a corner on the top shelf.” Thankfully he didn’t, and when he opened the thin leather-bound book missing its spine, he saw the inscription. He and Mary Jay stared at it jaws agape, then realized they had to get it to the Bodleian stat. Justifiably paranoid that they were holding an incredible literary and historical treasure, they carried it through the streets of Oxford to the Bodleian vaults in the only secure briefcase they had: Douglas Jay’s ministerial red box.

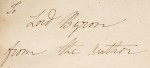

Sammy says he almost missed the “little volume lying at an angle in a corner on the top shelf.” Thankfully he didn’t, and when he opened the thin leather-bound book missing its spine, he saw the inscription. He and Mary Jay stared at it jaws agape, then realized they had to get it to the Bodleian stat. Justifiably paranoid that they were holding an incredible literary and historical treasure, they carried it through the streets of Oxford to the Bodleian vaults in the only secure briefcase they had: Douglas Jay’s ministerial red box. Once it arrived at the library unmolested, the Bodleian’s Keeper of Special Collections and Western Manuscripts Richard Ovenden verified that the dedication was in Mary Shelley’s distinctive hand. The multiple loops on the capital letter “t” in “To” are famously characteristic of Mary Shelley’s handwriting. Less than a year later, the discovery was announced to the public and the book put on sale at Peter Harrington.

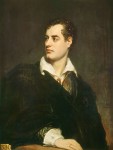

Once it arrived at the library unmolested, the Bodleian’s Keeper of Special Collections and Western Manuscripts Richard Ovenden verified that the dedication was in Mary Shelley’s distinctive hand. The multiple loops on the capital letter “t” in “To” are famously characteristic of Mary Shelley’s handwriting. Less than a year later, the discovery was announced to the public and the book put on sale at Peter Harrington.Miranda Seymour, a past visiting professor at Nottingham Trent University and biographer of Mary Shelley’s, introduced a fascinating glimpse into the relationship between Mary Shelley and Lord Byron. I don’t mean “relationship” in the sense of sexual relationship, although certainly at the time many, many people thought there was some form of threesome going on, whether it was Byron, Mary and her stepsister Claire Claremont, or Byron, Mary and Shelley. In fact, when the four of them (plus Doctor John Polidori) spent that famous summer of 1816 on the south shores of Lake Geneva at Villa Diodati, the English colony in Geneva on the north shores of the lake spent their time spying on the party through the new telescope at the hotel and tittering about the goings-on.

Almost a decade later, that gossip still held enough sway that it informed the private journal entry Mary Shelley wrote after she heard that Lord Byron had died in 1824. Shelley had been a widow for two years by then, and Byron had been of great help to her after Shelley’s tragic drowning off the coast of Liguria, sending her money and giving her work as a transcriber. Upon hearing the news that Byron had died of a fever (probably sepsis brought on by bleeding with non-sterile instruments) in Missolonghi, Greece while fighting for Greek independence, she wrote:

Almost a decade later, that gossip still held enough sway that it informed the private journal entry Mary Shelley wrote after she heard that Lord Byron had died in 1824. Shelley had been a widow for two years by then, and Byron had been of great help to her after Shelley’s tragic drowning off the coast of Liguria, sending her money and giving her work as a transcriber. Upon hearing the news that Byron had died of a fever (probably sepsis brought on by bleeding with non-sterile instruments) in Missolonghi, Greece while fighting for Greek independence, she wrote:This then was the coming event that cast its shadow over my last night’s miserable thoughts. Byron too has become one of the people of the grave, that miserable conclave to which the beings I love best belong. I knew him in the bright days of youth, when neither care nor fear had visited me, before death had made me feel my mortality and when the earth was the scene of all my hopes. Can I ever forget our evening visits to Diodati, our excursions on the lake when he sang the Tyrolese hymn to freedom and his voice was harmonized with the winds and the waves? Can I forget his attentions and consolations to me during my deepest misery? Never. Beauty sat on his countenance, and power beamed from his eye. His faults being for the most part weakness induced one readily to pardon them. Albe, the dear, capricious, fascinating Albe has left this desert world. God grant I too may die young and that region now ads that resplendent spirit whom I loved.(Albe was Mary’s nickname for Byron, a play on his initials LB and an anagram of Elba, the island to which Napoleon was exiled in 1814. Napoleon was a hero of Byron’s, which in Regency England you can imagine only added to the scandalousness of the man, and in fact the carriage that had brought him and his entourage to Diodati in 1816 was an exact replica of Napoleon’s coach.)

Even though she wrote this in her private journal, conscious of the likelihood that someday this material might be published as correspondence and diaries of famous people so often were, she crossed out “whom I loved” at the end of the passage and replaced it with “whose departure leaves the dull earth dark as midnight.”

Even though she wrote this in her private journal, conscious of the likelihood that someday this material might be published as correspondence and diaries of famous people so often were, she crossed out “whom I loved” at the end of the passage and replaced it with “whose departure leaves the dull earth dark as midnight.”Byron thought highly of her as well, which is notable because he tended to treat the women in his life pretty damn badly. He respected her intellect and her calm under pressure. She was just 18 when she left England with the married Shelley. It was a huge scandal. In addition to having to deal with the disapproval of her family and the general pearl-clutching and monocle-popping of English society, Mary had to navigate Shelley’s free love philosophy which included having sex with her sister. It was a complicated relationship and Byron admired how coolly she handled herself.

That regard he held her in is underscored by the survival of Byron’s copy of Frankenstein. He didn’t carry everything he owned to Greece with him. Many books and other possessions were shed in various places on the way and were dispersed locally. Yet, Frankenstein was in the shipment of five boxes of books sent to John Murray, publisher and executor of Byron’s estate, from Greece after Byron’s death. It was one of the select group of books he wanted to keep by his side.