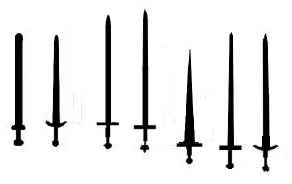

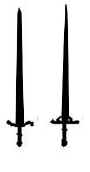

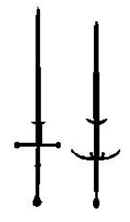

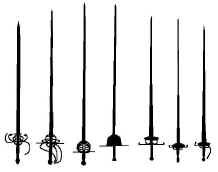

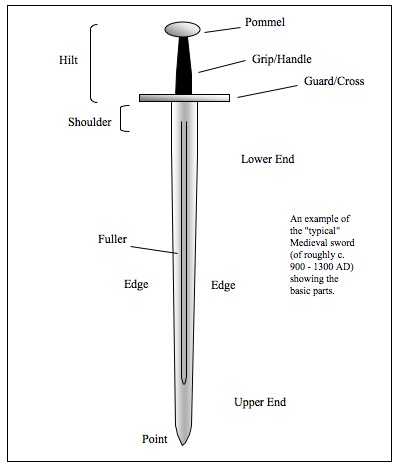

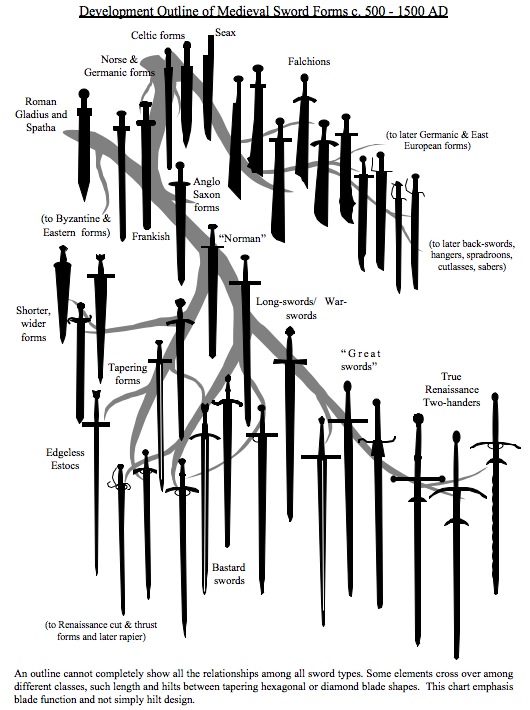

| The Spathology of Medieval and Renaissance Sword FormsIn the continuing effort to bring greater learning and scholarship to the serious study and practice of European weaponry, ARMA, as the premier Internet site for Medieval and Renaissance fighting arts, presents the following general definitions. This brief list is intended to aid students in study and dispel some of the many myths and misconceptions surrounding the subject. Swords from the Dark Ages to the High Middle Ages  Medieval swords existed in great varieties over a number of centuries. Both experimentation and specialization in design was constant. But certain common characteristics can describe the "generic" medieval sword as a long, wide, straight, double-edged blade with a simple cross-guard (or "cruciform" hilt). It might be designed for one or two-hands. The typical form was a single hand weapon used for hacking, shearing cuts and also for limited thrusting. This style developed essentially from Celtic, Germanic, Anglo-Saxon, and late Roman (the spatha) forms. The Viking and early Frankish forms (the "spata") are also considered to be more direct ancestors. Medieval swords can be classified (typically by hilt design) into a great many categories by curators, collectors, and military historians. However, students & re-creationists today should prefer the actual historical terms. At the time, long bladed weapons were simply referred to as "swords," or for the longer ones often a "sword of war," "war-sword" (French or), or even a "long-sword." Various languages might call them by Espée du Guerreschwert, svard, suerd, swerd, espada, esapadon, or epee. When later worn on the belt by mounted knights they might be called an Arming-sword. Arming-swords were also considered "riding-swords" (also parvaensis or epeecourte). It is this single-hand form which is so closely associated with the idea of the "knightly sword" (c. 1300). The challenge of armor in the Age-of-plate, forced many blades (both single-hand and longer) to be made narrower and pointier, but also thicker and more rigid. From at least the late 1300’s in England, a single-hand blade of this form was referred as a "short swerde." In 15th century Germany, it was the Kurczenswert. At this same time, as a result of the increased use of thrusting techniques some blades adopted guards with knuckle-bars, finger-rings, and/or sides-rings which lead to the compound-hilt. In later Elizabethan times, older one-handed medieval type blades became known as "short-swords" while the larger variety were still referred to as "long-swords." The term "short sword" was used later by 19th century collectors to refer to any style of "shorter" one-handed swords typically from ancient times on. Medieval swords existed in great varieties over a number of centuries. Both experimentation and specialization in design was constant. But certain common characteristics can describe the "generic" medieval sword as a long, wide, straight, double-edged blade with a simple cross-guard (or "cruciform" hilt). It might be designed for one or two-hands. The typical form was a single hand weapon used for hacking, shearing cuts and also for limited thrusting. This style developed essentially from Celtic, Germanic, Anglo-Saxon, and late Roman (the spatha) forms. The Viking and early Frankish forms (the "spata") are also considered to be more direct ancestors. Medieval swords can be classified (typically by hilt design) into a great many categories by curators, collectors, and military historians. However, students & re-creationists today should prefer the actual historical terms. At the time, long bladed weapons were simply referred to as "swords," or for the longer ones often a "sword of war," "war-sword" (French or), or even a "long-sword." Various languages might call them by Espée du Guerreschwert, svard, suerd, swerd, espada, esapadon, or epee. When later worn on the belt by mounted knights they might be called an Arming-sword. Arming-swords were also considered "riding-swords" (also parvaensis or epeecourte). It is this single-hand form which is so closely associated with the idea of the "knightly sword" (c. 1300). The challenge of armor in the Age-of-plate, forced many blades (both single-hand and longer) to be made narrower and pointier, but also thicker and more rigid. From at least the late 1300’s in England, a single-hand blade of this form was referred as a "short swerde." In 15th century Germany, it was the Kurczenswert. At this same time, as a result of the increased use of thrusting techniques some blades adopted guards with knuckle-bars, finger-rings, and/or sides-rings which lead to the compound-hilt. In later Elizabethan times, older one-handed medieval type blades became known as "short-swords" while the larger variety were still referred to as "long-swords." The term "short sword" was used later by 19th century collectors to refer to any style of "shorter" one-handed swords typically from ancient times on.The Viking Sword  From mostly the 8th to 11th centuries, Norse swords were noted for the unique design and the tempering patterns that were often visible in their blades. What made the weapon stand out was that it was resilient and robust against the kinds of armor and shields they regularly encountered. Wielded one-handed in conjunction with a shield it could make ferocious slashes and chops, deliver good thrusts, do all this without breaking or bending yet still hold a keen edge. It combined sturdy reliability and sharpness with lightness and strength to make a versatile weapon that in the right hands could penetrate hard chain or leather armor as well as softer furs and cloth. That it was also a beautiful object whose manufacture was part mystery only added to its allure. Though the Norse came to eventually adopt easier to produce designs of continental origin, and also used short single-edge blades, such as the scramasax or scramanseaxe (from which the Saxon people derive their name), it is the double edge variety with a wide flat pommel and short guard that became associated with them. From mostly the 8th to 11th centuries, Norse swords were noted for the unique design and the tempering patterns that were often visible in their blades. What made the weapon stand out was that it was resilient and robust against the kinds of armor and shields they regularly encountered. Wielded one-handed in conjunction with a shield it could make ferocious slashes and chops, deliver good thrusts, do all this without breaking or bending yet still hold a keen edge. It combined sturdy reliability and sharpness with lightness and strength to make a versatile weapon that in the right hands could penetrate hard chain or leather armor as well as softer furs and cloth. That it was also a beautiful object whose manufacture was part mystery only added to its allure. Though the Norse came to eventually adopt easier to produce designs of continental origin, and also used short single-edge blades, such as the scramasax or scramanseaxe (from which the Saxon people derive their name), it is the double edge variety with a wide flat pommel and short guard that became associated with them. A term popularly misapplied as a generic synonym for medieval swords or any long, wide military blade. The now popular misnomer "broadsword" in reference to Medieval blades actually originated with collectors in the early 19th century -although many mistranslations and misinterpretations of Medieval literature during the 19th and 20th centuries have inserted the word broadsword in place of other terms. They described swords of earlier ages as being "broader" than their own contemporary thinner ones. Many 17th-19th century blades such as spadroons, cutlasses, and straight sabers are classed as broadswords as are other closed hilt military swords. The weapon known as the true broadsword is in fact a form of short cutlass. The term "broadsword" does not appear in English military texts from the 1570s - 1630s and noes not show up in inventories of sword types from the 1630's, and likely came into use sometime between 1619 and 1630. Descriptions of swords as "broad" before this time are only incidental and the word "broad" is used as an adjective in the same way "sharp" or "large" would be applied. Leading arms curators almost always list the broadsword specifically as a close-hilted military sword from the second half of the 17th century. Those cage and basket hilted blades used by cavalry starting in the 1640's were in form, "broadswords." During this time a gentleman's blade had become the slender small-sword, whereas the military used various cutting blades. Today, arms collectors, museum curators theatrical-fighters, and fantasy-gamers have made the word broadsword a common, albeit blatantly historically incorrect, term for the Medieval sword. A term popularly misapplied as a generic synonym for medieval swords or any long, wide military blade. The now popular misnomer "broadsword" in reference to Medieval blades actually originated with collectors in the early 19th century -although many mistranslations and misinterpretations of Medieval literature during the 19th and 20th centuries have inserted the word broadsword in place of other terms. They described swords of earlier ages as being "broader" than their own contemporary thinner ones. Many 17th-19th century blades such as spadroons, cutlasses, and straight sabers are classed as broadswords as are other closed hilt military swords. The weapon known as the true broadsword is in fact a form of short cutlass. The term "broadsword" does not appear in English military texts from the 1570s - 1630s and noes not show up in inventories of sword types from the 1630's, and likely came into use sometime between 1619 and 1630. Descriptions of swords as "broad" before this time are only incidental and the word "broad" is used as an adjective in the same way "sharp" or "large" would be applied. Leading arms curators almost always list the broadsword specifically as a close-hilted military sword from the second half of the 17th century. Those cage and basket hilted blades used by cavalry starting in the 1640's were in form, "broadswords." During this time a gentleman's blade had become the slender small-sword, whereas the military used various cutting blades. Today, arms collectors, museum curators theatrical-fighters, and fantasy-gamers have made the word broadsword a common, albeit blatantly historically incorrect, term for the Medieval sword. Long-Swords  The various kinds of long bladed Medieval swords that had handles long enough to be used in two hands were deemed long-swords (German Langenschwert/ Langes Swert or Italian spada longa). Long-swords, war-swords, or great swords are characterized by having both a long grip and a long blade. We know at the time that Medieval warriors did distinguished war-swords or great-swords ("grant espees" or "grete swerdes") from "standard" swords in general, but long-swords were really just those larger versions of typical one-handed swords, except with stouter blades. They were "longer swords," as opposed to single-hand swords, or just "swords." They could be used on foot or mounted and sometimes even with a shield. The term war-sword from the 1300's referred to larger swords that were carried in battle. They were usually kept on the saddle as opposed to worn on the belt. A 15th century Burgundian manual refers to both "great and small swords." As a convenient classification, long-swords include great-swords, bastard-swords, and estocs. In the 1200’s in England blunt swords for non-lethal tournaments were sometimes known as "arms of courtesy." There is a reference to an English tournament of 1507 in which among the events contestants are challenged to "8 strookes with Swords rebated." Wooden training weapons were sometimes called wasters in the 1200's or batons in the 1300's and 1400's. Knightly combat with blunt or "foyled" weapons for pleasure was known as à plaisance, combat to the death was à lóuutrance. In Germanic lands during, special practice longswords with flexible blunt blades and rounded points were usually known as Federschwerter or "feather-swords." The various kinds of long bladed Medieval swords that had handles long enough to be used in two hands were deemed long-swords (German Langenschwert/ Langes Swert or Italian spada longa). Long-swords, war-swords, or great swords are characterized by having both a long grip and a long blade. We know at the time that Medieval warriors did distinguished war-swords or great-swords ("grant espees" or "grete swerdes") from "standard" swords in general, but long-swords were really just those larger versions of typical one-handed swords, except with stouter blades. They were "longer swords," as opposed to single-hand swords, or just "swords." They could be used on foot or mounted and sometimes even with a shield. The term war-sword from the 1300's referred to larger swords that were carried in battle. They were usually kept on the saddle as opposed to worn on the belt. A 15th century Burgundian manual refers to both "great and small swords." As a convenient classification, long-swords include great-swords, bastard-swords, and estocs. In the 1200’s in England blunt swords for non-lethal tournaments were sometimes known as "arms of courtesy." There is a reference to an English tournament of 1507 in which among the events contestants are challenged to "8 strookes with Swords rebated." Wooden training weapons were sometimes called wasters in the 1200's or batons in the 1300's and 1400's. Knightly combat with blunt or "foyled" weapons for pleasure was known as à plaisance, combat to the death was à lóuutrance. In Germanic lands during, special practice longswords with flexible blunt blades and rounded points were usually known as Federschwerter or "feather-swords." Great-Swords  Those blades long and weighty enough to demand a double grip are great-swords. They are infantry swords which cannot be used in a single-hand. Originally the term "great-sword" (gret sord, grete swerde, or grant espée), only meant a war-sword (long-sword), but it has now more or less come to mean a sub-class of those larger long-swords/war-swords that are still not true two-handers. They were even known as Grete Swerdes of Warre or Grans Espees de Guerre. Although they are "two hand" swords, great-swords not are the specialized weapons of later two-handed swords. They are the swords that are antecedents to the even larger Renaissance versions. Great-swords are also the weapons often depicted in various German sword manuals. A Medieval great-sword might also be called a "twahandswerds" or "too honde swerd." Whereas other long-swords could be used on horseback and some even with shields, great swords however were infantry weapons only. Their blades might be flat and wide or later on, more narrow and hexagonal or diamond shaped. These larger swords capable of facing heavier weapons such as pole-arms and larger axes were devastating against lighter armors. Long, two-handed swords with narrower, flat hexagonal blades and thinner tips (such as the Italian "spadone") were a response to plate-armor. Against plate armor such rigid, narrow, and sharply pointed swords are not used in the same chop and cleave manner as with flatter, wider long-swords and great swords. Instead, they are handled with tighter movements that emphasize their thrusting points and allow for greater use of the hilt. Those of the earlier parallel-edged shape are known more as war-swords, while later the thicker, tapering, sharply pointed form were more often called bastard-swords. One type of long German sword, the "Rhenish Langenschwert," from the Rhenish city of Cologne, had a blade of some 4 feet and an enormous grip of some 14 to 16 inches long, not including the pommel. Those blades long and weighty enough to demand a double grip are great-swords. They are infantry swords which cannot be used in a single-hand. Originally the term "great-sword" (gret sord, grete swerde, or grant espée), only meant a war-sword (long-sword), but it has now more or less come to mean a sub-class of those larger long-swords/war-swords that are still not true two-handers. They were even known as Grete Swerdes of Warre or Grans Espees de Guerre. Although they are "two hand" swords, great-swords not are the specialized weapons of later two-handed swords. They are the swords that are antecedents to the even larger Renaissance versions. Great-swords are also the weapons often depicted in various German sword manuals. A Medieval great-sword might also be called a "twahandswerds" or "too honde swerd." Whereas other long-swords could be used on horseback and some even with shields, great swords however were infantry weapons only. Their blades might be flat and wide or later on, more narrow and hexagonal or diamond shaped. These larger swords capable of facing heavier weapons such as pole-arms and larger axes were devastating against lighter armors. Long, two-handed swords with narrower, flat hexagonal blades and thinner tips (such as the Italian "spadone") were a response to plate-armor. Against plate armor such rigid, narrow, and sharply pointed swords are not used in the same chop and cleave manner as with flatter, wider long-swords and great swords. Instead, they are handled with tighter movements that emphasize their thrusting points and allow for greater use of the hilt. Those of the earlier parallel-edged shape are known more as war-swords, while later the thicker, tapering, sharply pointed form were more often called bastard-swords. One type of long German sword, the "Rhenish Langenschwert," from the Rhenish city of Cologne, had a blade of some 4 feet and an enormous grip of some 14 to 16 inches long, not including the pommel.Bastard Swords  In the early 1400's (as early as 1418) a form of long-sword often with specially shaped grips for one or two hands, became known as an Espée Bastarde or "bastard sword." The term may derive not form the blade length, but because bastard-swords typically had longer handles with special "half-grips" which could be used by either one or both hands. In this sense they were neither a one-handed sword nor a true great-sword/two-handed sword, and thus not a member of either "family" of sword. Evidence shows the their blade were typically tapered. Since newer types of shorter swords were coming into use, the term "bastard-sword" came to distinguish this form of long-sword. Bastard-swords typically had longer handles with special "half-grips" which could be used by either one or both hands. These handles have recognizable "waist" and "bottle" shapes (such grips were later used on the Renaissance two-handed sword). The unique bastard-sword half-grip was a versatile and practical innovation. Although, once again classification is not clear since the term "bastard-sword" appears to have not been entirely exclusive to those swords with so-called "hand-and-a-half" handles as older styles of long-sword were still in limited use. Bastard-swords varied and they might have either a flat blade or narrow hexagonal one for fighting plate-armor. Some were intended more for cutting while others were better for thrusting. Bastard swords continued to be used by knights and men-at-arms into the 1500's. Their hilt style leads toward the shorter cut & thrust sword forms of the Renaissance. Strangely, in the early Renaissance the term bastard-sword was also sometimes used to refer to single-hand arming-swords with compound-hilts. A form of German arming sword with a bastard-style compound hilt was called a "Reitschwert" ("cavalry sword") or a "Degen" ("knight's sword"). Although these might have been forms of single-hand estoc. In the early 1400's (as early as 1418) a form of long-sword often with specially shaped grips for one or two hands, became known as an Espée Bastarde or "bastard sword." The term may derive not form the blade length, but because bastard-swords typically had longer handles with special "half-grips" which could be used by either one or both hands. In this sense they were neither a one-handed sword nor a true great-sword/two-handed sword, and thus not a member of either "family" of sword. Evidence shows the their blade were typically tapered. Since newer types of shorter swords were coming into use, the term "bastard-sword" came to distinguish this form of long-sword. Bastard-swords typically had longer handles with special "half-grips" which could be used by either one or both hands. These handles have recognizable "waist" and "bottle" shapes (such grips were later used on the Renaissance two-handed sword). The unique bastard-sword half-grip was a versatile and practical innovation. Although, once again classification is not clear since the term "bastard-sword" appears to have not been entirely exclusive to those swords with so-called "hand-and-a-half" handles as older styles of long-sword were still in limited use. Bastard-swords varied and they might have either a flat blade or narrow hexagonal one for fighting plate-armor. Some were intended more for cutting while others were better for thrusting. Bastard swords continued to be used by knights and men-at-arms into the 1500's. Their hilt style leads toward the shorter cut & thrust sword forms of the Renaissance. Strangely, in the early Renaissance the term bastard-sword was also sometimes used to refer to single-hand arming-swords with compound-hilts. A form of German arming sword with a bastard-style compound hilt was called a "Reitschwert" ("cavalry sword") or a "Degen" ("knight's sword"). Although these might have been forms of single-hand estoc. The familiar modern term "hand-and-a-half" was more or less coined to describe bastards swords specifically. The term "hand-and-a-half sword" is often used in reference to long-swords is not historical and is sometimes misapplied to other swords (although during the late 1500's, long after such blades fell out of favor, some German forms of this phrase are believed to have been used). While there is no evidence of the term “hand-and-a-half” having been used during the Middle Ages, either in English or other languages, it does appear in the 16th century. In his 1904 bibliography of Spanish texts, D. Enrique de Leguina gives a 1564 reference to una espada estoque de mano y media, and a 1594 reference to una espada de mano y media. In the Ragionamento, the unpublished appendix to his 1580, Traite d Escrime (“Fencing Treatise”), Giovanni Antonio Lovino describes one sword as una spada di una mano et mana et meza (literally “hand and a half sword”) which he distinguishes from the much larger spada da due mani or two-handed sword (the immense Renaissance weapon). The term spadone was used by Fiore Dei Liberi in 1410 to refer to a tapering long-sword and Camillo Agrippa in 1550 called the spadone a war sword. Later it was defined by John Florio in his 1598 Italian-English dictionary as “a long or two-hand sword.” Two-handed Swords  The term "two-hander" or "two-handed sword" (espée a deure mains or spada da due mani) was in use as early as 1400 and is really a classification of sword applied both to Medieval great-swords as well Renaissance swords (the true two-handed swords). Such weapons saw more use in the later Middle Ages and early Renaissance. Technically, true two-handed swords (epee's a deux main) were actually Renaissance, not Medieval weapons. They are really those specialized forms of the later 1500-1600's, such as the Swiss/German Dopplehander ("double-hander") or Bidenhander ("both-hander") or Zweihander / Zweyhander are relatively modern not historical terms. English ones were sometimes referred to as "slaughterswords" after the German Schlachterschwerter ("battle swords"). These weapons were used primarily for fighting against pike-squares where they would hack paths through lobbing the tips off the poles. In Germany, England, and elsewhere schools also taught their use for single-combat. In True two-handed swords have compound-hilts with side-rings and enlarged cross-guards of up to 12 inches. Most have small, pointed lugs or flanges protruding from their blades 4-8 inches below their guard. These parrierhaken or "parrying hooks" act almost as a secondary guard for the ricasso to prevent other weapons from sliding down into the hands. They make up for the weapon's slowness on the defence and can allow another blade to be momentarily trapped or bound up. They can also be used to strike with. The most well-known of "twa handit swordis" is the Scottish Claymore (Gaelic for "claidheamh-more" or great-sword) which developed out of earlier Scottish great-swords with which they are often compared. They were used by the Scottish Highlanders against the English in the 1500's. Another sword of the same name is the later Scots basket-hilt broadsword (a relative of the Renaissance Slavic-Italian schiavona) whose hilt completely enclosed the hand in a cage-like guard. Both swords have come to be known by the same name since the late 1700's. Certain wave or flame-bladed two-handed swords have come to be known by collectors as flamberges, although this is inaccurate. Such swords developed in the early-to-mid 1500's and are more appropriately known as flammards or flambards (the German Flammenschwert). The flamberge was also a term later applied to certain types of rapiers. The wave-blade form is visually striking but really no more effective in its cutting than a straight one. There were also huge two-handed blades known as "bearing-swords" or "parade-swords" (Paratschwert), weighing up to 12 or even 15 pounds and which were intended only for carrying in ceremonial processions and parades. In the 1500’s there were also a few rare single-edged two-handers such as the Swiss-German Grosse Messer or later sometimes called a Zwiehand sabel. The term "two-hander" or "two-handed sword" (espée a deure mains or spada da due mani) was in use as early as 1400 and is really a classification of sword applied both to Medieval great-swords as well Renaissance swords (the true two-handed swords). Such weapons saw more use in the later Middle Ages and early Renaissance. Technically, true two-handed swords (epee's a deux main) were actually Renaissance, not Medieval weapons. They are really those specialized forms of the later 1500-1600's, such as the Swiss/German Dopplehander ("double-hander") or Bidenhander ("both-hander") or Zweihander / Zweyhander are relatively modern not historical terms. English ones were sometimes referred to as "slaughterswords" after the German Schlachterschwerter ("battle swords"). These weapons were used primarily for fighting against pike-squares where they would hack paths through lobbing the tips off the poles. In Germany, England, and elsewhere schools also taught their use for single-combat. In True two-handed swords have compound-hilts with side-rings and enlarged cross-guards of up to 12 inches. Most have small, pointed lugs or flanges protruding from their blades 4-8 inches below their guard. These parrierhaken or "parrying hooks" act almost as a secondary guard for the ricasso to prevent other weapons from sliding down into the hands. They make up for the weapon's slowness on the defence and can allow another blade to be momentarily trapped or bound up. They can also be used to strike with. The most well-known of "twa handit swordis" is the Scottish Claymore (Gaelic for "claidheamh-more" or great-sword) which developed out of earlier Scottish great-swords with which they are often compared. They were used by the Scottish Highlanders against the English in the 1500's. Another sword of the same name is the later Scots basket-hilt broadsword (a relative of the Renaissance Slavic-Italian schiavona) whose hilt completely enclosed the hand in a cage-like guard. Both swords have come to be known by the same name since the late 1700's. Certain wave or flame-bladed two-handed swords have come to be known by collectors as flamberges, although this is inaccurate. Such swords developed in the early-to-mid 1500's and are more appropriately known as flammards or flambards (the German Flammenschwert). The flamberge was also a term later applied to certain types of rapiers. The wave-blade form is visually striking but really no more effective in its cutting than a straight one. There were also huge two-handed blades known as "bearing-swords" or "parade-swords" (Paratschwert), weighing up to 12 or even 15 pounds and which were intended only for carrying in ceremonial processions and parades. In the 1500’s there were also a few rare single-edged two-handers such as the Swiss-German Grosse Messer or later sometimes called a Zwiehand sabel.The Claymore  Identified with the Scot's symbol of the warrior, the term "Claymore" is Gaelic for "claidheamh-more" (great sword). This two-handed broadsword was used by the Scottish Highlanders against the English in the 16th century and is often confused with a Basket-hilt "broadsword" (a relative of the Italian schiavona) whose hilt completely enclosed the hand in a cage- like guard. Both swords have come to be known by the same name since the late 1700's. Identified with the Scot's symbol of the warrior, the term "Claymore" is Gaelic for "claidheamh-more" (great sword). This two-handed broadsword was used by the Scottish Highlanders against the English in the 16th century and is often confused with a Basket-hilt "broadsword" (a relative of the Italian schiavona) whose hilt completely enclosed the hand in a cage- like guard. Both swords have come to be known by the same name since the late 1700's.The Falchion  A rarer form of sword that was little more than a meat cleaver, possibly even a simple kitchen and barnyard tool adopted for war. Indeed, it may come from a French word for a sickle, "fauchon." It can be seen in Medieval art being used against lighter armors by infidels as well as footman and even knights. The weapon is entirely European and not derived from eastern sources. More common in the Renaissance, it was considered a weapon to be proficient with in addition to the sword. The falchion is similar to the German Dusack (or Dusagge), and has been dubiously suggested as possibly related to the Dark Age long knife, "seax" (scramanseax), and even later curved blades such as sabres (or sabels). Similar to an Arabian "scimitar," the falchion's wide, heavy blade weighted more towards the point could deliver tremendous blows. Several varieties were known, most all with single edges and rounded points. A later Italian falchion with a slender sabre-like blade was called a "storta" or a "malchus." Another similar weapon in German was the saber-like Messer. Large two-hand versions, called Grosse Messers, with straight or curved single-edged blades were known by 1500. A rarer form of sword that was little more than a meat cleaver, possibly even a simple kitchen and barnyard tool adopted for war. Indeed, it may come from a French word for a sickle, "fauchon." It can be seen in Medieval art being used against lighter armors by infidels as well as footman and even knights. The weapon is entirely European and not derived from eastern sources. More common in the Renaissance, it was considered a weapon to be proficient with in addition to the sword. The falchion is similar to the German Dusack (or Dusagge), and has been dubiously suggested as possibly related to the Dark Age long knife, "seax" (scramanseax), and even later curved blades such as sabres (or sabels). Similar to an Arabian "scimitar," the falchion's wide, heavy blade weighted more towards the point could deliver tremendous blows. Several varieties were known, most all with single edges and rounded points. A later Italian falchion with a slender sabre-like blade was called a "storta" or a "malchus." Another similar weapon in German was the saber-like Messer. Large two-hand versions, called Grosse Messers, with straight or curved single-edged blades were known by 1500.Cut & Thrust Swords of the Renaissance  The generic term "cut and thrust sword" is a general one which can be applied to a whole range of blade forms (field swords, side-swords, spada di lato, arming swords). However, the Renaissance military sword is generally characterized by a swept or compound-hilt, a narrow cut-and-thrust blade with stronger cross-section, and tapering tip. A direct descendant of the Medieval knightly sword, the cut and thrust sword was used by lightly armed footmen as well as civilians in the 16th and 17th centuries. During this time they were employed against a range of armored and unarmored opponents. They were popular for sword and buckler and sword and dagger fighting. They utilized an innovative one-handed grip fingering the ricasso (a dull portion of blade just above the guard). Renaissance cut and thrust swords should not be referred to as "early Renaissance swords" since they were actually in use throughout the period. Military and civilian forms of them existed before, during and after the development of the rapier. For example, similar blades (with and without ricassos and compound hilts) saw use in the English Civil War and even later. They should also not be referred to as "sword-rapiers" or "early rapiers," although in a sense, some of them were. Renaissance cut & thrust swords were their own distinct sword type. Although sometimes considered a "transition" form, this is inaccurate as they were both the ancestor and contemporary of the rapier for which they are often misidentified. Some forms of cage and basket hilts blades are occasionally referred to as "riding swords" by collectors and curators, and sometimes even as "broadswords." However, the 16th century Italians did sometimes distinguish between spada da cavallo, or a blade for horsemen, spada da fante, an infantry sword for foot-soldiers, and later spada da lato (side sword), a civilian cut-and-thrust sword, a form of which only later became the rapier (in modern times sometimes called a stricia). The generic term "cut and thrust sword" is a general one which can be applied to a whole range of blade forms (field swords, side-swords, spada di lato, arming swords). However, the Renaissance military sword is generally characterized by a swept or compound-hilt, a narrow cut-and-thrust blade with stronger cross-section, and tapering tip. A direct descendant of the Medieval knightly sword, the cut and thrust sword was used by lightly armed footmen as well as civilians in the 16th and 17th centuries. During this time they were employed against a range of armored and unarmored opponents. They were popular for sword and buckler and sword and dagger fighting. They utilized an innovative one-handed grip fingering the ricasso (a dull portion of blade just above the guard). Renaissance cut and thrust swords should not be referred to as "early Renaissance swords" since they were actually in use throughout the period. Military and civilian forms of them existed before, during and after the development of the rapier. For example, similar blades (with and without ricassos and compound hilts) saw use in the English Civil War and even later. They should also not be referred to as "sword-rapiers" or "early rapiers," although in a sense, some of them were. Renaissance cut & thrust swords were their own distinct sword type. Although sometimes considered a "transition" form, this is inaccurate as they were both the ancestor and contemporary of the rapier for which they are often misidentified. Some forms of cage and basket hilts blades are occasionally referred to as "riding swords" by collectors and curators, and sometimes even as "broadswords." However, the 16th century Italians did sometimes distinguish between spada da cavallo, or a blade for horsemen, spada da fante, an infantry sword for foot-soldiers, and later spada da lato (side sword), a civilian cut-and-thrust sword, a form of which only later became the rapier (in modern times sometimes called a stricia).The Back-Sword  The back-sword or Backe swerd was a less-common form of single-edged renaissance military cut & thrust blade with a compound-hilt (side-rings or anneus, finger-rings, knuckle-bar, etc.). Most popular in England with a buckler or target from at least the 1520’s, it was long enough for both mounted and infantry and favored because its single-edge designed allowed for a superior cutting blow. It was also popular in Germany. Back-swords may be related to later single-edged European blade forms and came in a variety of hilts and lengths. They also include later Hangers and hunting swords, as well as Mortuary-hilt and Walloon-hilt broadswords. The back-sword or Backe swerd was a less-common form of single-edged renaissance military cut & thrust blade with a compound-hilt (side-rings or anneus, finger-rings, knuckle-bar, etc.). Most popular in England with a buckler or target from at least the 1520’s, it was long enough for both mounted and infantry and favored because its single-edge designed allowed for a superior cutting blow. It was also popular in Germany. Back-swords may be related to later single-edged European blade forms and came in a variety of hilts and lengths. They also include later Hangers and hunting swords, as well as Mortuary-hilt and Walloon-hilt broadswords.The Schiavona  A form of agile Renaissance cut & thrust sword with a decorative cage-hilt and distinctive "cat-head" pommel. So named for the Schiavoni or Venetian Doge’s Slavonic mercenaries and guards of the 1500’s who favored the weapon. They are usually single edged back-swords but may also be wide or narrow double edged blades. Some have ricasso for a fingering grip while others have thumb-rings. The Schiavona is often considered the antecedent to other cage hilt swords such as the Scottish basket-hilted "broadsword." A form of agile Renaissance cut & thrust sword with a decorative cage-hilt and distinctive "cat-head" pommel. So named for the Schiavoni or Venetian Doge’s Slavonic mercenaries and guards of the 1500’s who favored the weapon. They are usually single edged back-swords but may also be wide or narrow double edged blades. Some have ricasso for a fingering grip while others have thumb-rings. The Schiavona is often considered the antecedent to other cage hilt swords such as the Scottish basket-hilted "broadsword."The Katzbalger  A form of typically one-handed sword with a shorter blade and invariably "S" shaped guard. It was favored by pikemen and the Swiss/German Landesknetchs for fighting close in amidst pike-squares. Many were originally longer, wider blades which were cut down and remounted. The name likely derives from a word associated with cat-gut or cat-skin. Their lengths varied from short to mid-sized. A form of typically one-handed sword with a shorter blade and invariably "S" shaped guard. It was favored by pikemen and the Swiss/German Landesknetchs for fighting close in amidst pike-squares. Many were originally longer, wider blades which were cut down and remounted. The name likely derives from a word associated with cat-gut or cat-skin. Their lengths varied from short to mid-sized.The Rapier  Popular in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the rapier was a dueling weapon whose form was developed from cut and thrust swords. Its use was more brutal and forceful than the light sport fencing that we know of today. Originally, starting about 1470, any civilian sword was often referred to as simply a "rapier," but it quickly took on the meaning of a slender, civilian thrusting sword. There is also an English document from the 1500's that uses the term "rapier-sword" for advising courtiers how to be armed, indicating the understanding that there were new slender blades coming into civilian use. Eventually developing into an edgeless, ideal thrusting weapon, the quick, innovative rapier superseded the military cut & thrust sword for personal duel and urban self-defense. Being capable of making only limited lacerations, earlier varieties of rapier are still often confused with the cut and thrust swords which gave gestation to their method. As a civilian weapon of urban self-defense, a true rapier was a tip-based thrusting sword that used stabbing and piercing, not slashing and cleaving. True rapier blades ranged from early flatter triangular blades to thicker, narrow hexagonal ones. Rapier hilts range from swept styles, to later dishes and cups. It had no true cutting edge such as with military swords for war. Popular in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the rapier was a dueling weapon whose form was developed from cut and thrust swords. Its use was more brutal and forceful than the light sport fencing that we know of today. Originally, starting about 1470, any civilian sword was often referred to as simply a "rapier," but it quickly took on the meaning of a slender, civilian thrusting sword. There is also an English document from the 1500's that uses the term "rapier-sword" for advising courtiers how to be armed, indicating the understanding that there were new slender blades coming into civilian use. Eventually developing into an edgeless, ideal thrusting weapon, the quick, innovative rapier superseded the military cut & thrust sword for personal duel and urban self-defense. Being capable of making only limited lacerations, earlier varieties of rapier are still often confused with the cut and thrust swords which gave gestation to their method. As a civilian weapon of urban self-defense, a true rapier was a tip-based thrusting sword that used stabbing and piercing, not slashing and cleaving. True rapier blades ranged from early flatter triangular blades to thicker, narrow hexagonal ones. Rapier hilts range from swept styles, to later dishes and cups. It had no true cutting edge such as with military swords for war.  The so-called "sword-rapier" is actually a term invented by collectors in the last century and is not a historical one. Increasingly, many Renaissance cut and thrust swords are mistakenly labeled as such. With the ascendancy of rapiers over swords in personal duel and private quarrel, there were many attempts to combine the slashing and cleaving potential of a traditional military sword with the quick, agile thrust of a dueling rapier. This lead to a great deal of experimental blade forms, many of which were dismal failures with neither the cutting power of wider swords, nor the speed and lightness of true rapiers. Made to do both, they typically did neither very well and few examples of these blades forms survive. They do appear to have been popular with high-ranking military officers during the mid 17th century (who of course, would be among those least likely to engage in battlefield hand-to- hand combat). They are also sometimes mistakenly called "cutting rapiers" or assumed to be some form of "transition" blade between swords and rapiers. The so-called "sword-rapier" is actually a term invented by collectors in the last century and is not a historical one. Increasingly, many Renaissance cut and thrust swords are mistakenly labeled as such. With the ascendancy of rapiers over swords in personal duel and private quarrel, there were many attempts to combine the slashing and cleaving potential of a traditional military sword with the quick, agile thrust of a dueling rapier. This lead to a great deal of experimental blade forms, many of which were dismal failures with neither the cutting power of wider swords, nor the speed and lightness of true rapiers. Made to do both, they typically did neither very well and few examples of these blades forms survive. They do appear to have been popular with high-ranking military officers during the mid 17th century (who of course, would be among those least likely to engage in battlefield hand-to- hand combat). They are also sometimes mistakenly called "cutting rapiers" or assumed to be some form of "transition" blade between swords and rapiers.The Flamberge The Baroque Small Sword While it is the straight-bladed cruciform sword style that for both war and duel was perfected in Europe as no where else, curved swords were hardly unknown. Many forms were known from the ancient convex-bladed Greek kopis and Iberian falcatta, to the laengsaex curved Viking blade, as well as the short-sword/long-knife seax or scramsax. There is also the Medieval falchion and the German curved Messer, Grossmessr, and bohemian Dusask The Italians used the curved storta, the straight bladed but curved-edge braquemart and the curved badelair (baudelair, bazelair, or basilaire) as well as the short curved braquet. Finally, wide varieties of sabers, sabres, sabels, and cutlasses were used from at least the mid-1500’s. Indigenous European curved sword forms such as the Czech tesak, Polish tasak, and Russian tisak were used since at least the 7th century.  Sword Parts Sword Parts Many sword types are closely identified with a particular style of hilt. Yet hilts were very often replaced on blades over time a weapon. Thus, a sword cannot be classified or categorized by whatever kind of cross, pommel, or grip it has, but by the length, form, and geometry of its blade. Hilt - The upper portion of a sword consisting of the cross-guard, handle/grip, and pommel (most Medieval swords have a straight cross or cruciform-hilt).Called the Handhabein German. In Old French the crosspiece was called helz, the grip called poing, the pommel called pom, and the handle might be bound with metal rings called mangon. Cross - The typically straight bar or "guard" of a Medieval sword, also called a "cross-guard." A Renaissance term for the straight or curved cross-guard was the quillons (possibly from an old French or Latin term for a type of reed). Fiore Dei Liberi in 1410 referred to it as the crucibus. Fillipo Vadi in the 1480s termed it the cross-guard or "crosses," Elza term. Called the Gehiltz or Gehultz in German. Called the Kreuz in Germanand Croce in Italian. Quillons: A Renaissance term for the two cross-guards (forward and back) whether straight or curved. It is likely from an old French or Latin term for a reed. On Medieval swords the cross guard may be called simply the "cross," or just the "guard." Pommel: Latin for "little apple," the counter-weight which secures the hilt to the blade and allows the hand either rest on it or grip it. Forte': A Renaissance term for the upper portion on a sword blade which has more control and strength and which does most  Foible: A Renaissance term for the lower portion on a sword blade which is weaker (or "feeble") but has more agility and speed and which does most of the attacking. Foible: A Renaissance term for the lower portion on a sword blade which is weaker (or "feeble") but has more agility and speed and which does most of the attacking.Fuller - A shallow central-groove or channel on a blade which lightens it as well as improves strength and flex. Sometimes mistakenly called a "blood-run" or "blood-groove," it has nothing to do with blood flow, cutting power, or a blade sticking. A sword might have one, none, or several fullers running a portion of its length, on either one or both sides. Narrow deep fullers are also sometimes referred to as flukes. The opposite of a fuller is a riser, which improves rigidity. Grip - The handle of a sword, usually made of leather, wire, bone, horn, or ivory (also, a term for the method of holding the sword). Lower end - the tip portion or final quarter of blade on a sword Pommel - Latin for "little apple," the counter-weight which secures the hilt to the blade and allows the hand to either rest on it or grip it. Sometimes it includes a small rivet (capstan rivet) called a pommel nut, pommel bolt, or tang nut. On some Medieval swords the pommel may be partially or fully gripped and handled. Ricasso - The dull portion of a blade just above the hilt. It is intended for wrapping the index finger around to give greater tip control (called "fingering"). Not all sword forms had ricasso. They can be found on many Bastard-swords, most cut & thrust swords and later rapiers. Those on Two-Handed swords are sometimes called a "false-grip," and usually allow the entire second had to grip and hold on. The origin of the term is obscure. Shoulder - The corner portion of a sword separating the blade from the tang. Tang - The un-edged hidden portion or ("tongue") of a blade running through the handle and to which the pommel is attached. The place where the tang connects to the blade is called the "shoulder." A sword's tang is sometimes of a different temper than the blade itself. The origin of the term is obscure. Upper end - The hilt portion of a Medieval sword Waisted-grip - A specially shaped handle on some bastard or hand-and-a-half swords, consisting of a slightly wider middle and tapering towards the pommel. Annellet/Finger-Ring: The small loops extending toward the blade from the quillons intended to protect a finger wrapped over the guard. They developed in the middle-ages and can be found on many styles of Late-Medieval swords. They are common on Renaissance cut & thrust swords and rapiers they and also small-swords. For some time they have been incorrectly called the "pas d`ane." Compound-Hilt/Complex-Guard: A term used for the various forms of hilt found on Renaissance and some late-Medieval swords. They consist typically of finger-rings, side-rings or ports, a knuckle-bar, and counter-guard or back-guard. Swept-hilts, ring-hilts, cage-hilts, and some basket-hilts are forms of complex-guard.  |

Saturday, February 9, 2013

Sword Forms

Sword Forms

Wednesday, February 6, 2013

Remnants of Abandoned Star Wars Sets in Morocco and Tunisia Reminiscent of Ancient Ruins | Feature Shoot

Remnants of Abandoned Star Wars Sets in Morocco and Tunisia Reminiscent of Ancient Ruins | Feature Shoot

Italian, New York-based photographer Rä di Martino rouses the Star Wars fan in all of us in Every World’s A Stage, a series of photos of the abandoned Hollywood sets constructed for the epic George Lucas film. Martino spent over a year traveling throughout the desert towns of Morocco and Tunisia, exploring these massive structures that stand almost like ancient ruins. Martino found the juxtaposition of these cinematic byproducts with the actual ruins existing in these towns quite fascinating—and we do too. What’s not intriguing about the remnants of an otherworldly place amidst a worldly one?

via Phaidon

Remnants of Abandoned Star Wars Sets in Morocco and Tunisia Reminiscent of Ancient Ruins

by Amanda Gorence on February 1, 2013 · 5 comments

Italian, New York-based photographer Rä di Martino rouses the Star Wars fan in all of us in Every World’s A Stage, a series of photos of the abandoned Hollywood sets constructed for the epic George Lucas film. Martino spent over a year traveling throughout the desert towns of Morocco and Tunisia, exploring these massive structures that stand almost like ancient ruins. Martino found the juxtaposition of these cinematic byproducts with the actual ruins existing in these towns quite fascinating—and we do too. What’s not intriguing about the remnants of an otherworldly place amidst a worldly one?

via Phaidon

Tuesday, February 5, 2013

People of Timbuktu save manuscripts from invaders

People of Timbuktu save manuscripts from invaders

FILE - In this Friday, Feb. 1, 2013 file photo, Abdoulaye Cisse, who lives in the Timbuktu area, holds open a book at the Hamed Baba book repository, one of the world's most precious collections of ancient manuscripts, in Timbuktu, Mali. Islamists claimed they burned most of the holy books there, and for eight days the fire alarm blared inside the repository. But because of the ingenuity of the people of Timbuktu, who hid manuscripts in millet bags, the al-Qaida-linked extremists succeeded in destroying only 5 percent of the collection. (AP Photo/Harouna Traore, File)

The al-Qaida-linked extremists who ransacked the institute wanted to deal a final blow to Mali, whose northern half they had held for 10 months before retreating in the face of a French-led military advance. They also wanted to deal a blow to the world, especially France, whose capital houses the headquarters of UNESCO, the organization which recognized and elevated Timbuktu's monuments to its list of World Heritage sites.

So as they left, they torched the Ahmed Baba Institute of Higher Learning and Islamic Research, aiming to destroy a heritage of 30,000 manuscripts that date back to the 13th century.

"These manuscripts are our identity," said Abdoulaye Cisse, the library's acting director. "It's through these manuscripts that we have been able to reconstruct our own history, the history of Africa . People think that our history is only oral, not written. What proves that we had a written history are these documents."

The first people who spotted the column of black smoke on Jan. 23 were the residents whose homes surround the library, and they ran to tell the center's employees. The bookbinders, manuscript restorers and security guards who work for the institute broke down and cried.

Just about the only person who didn't was Cisse, the acting director, who for months had harbored a secret. Starting last year, he and a handful of associates had conspired to save the documents so crucial to this 1,000-year-old town.

In April, when the rebels preaching a radical version of Islam first rolled into this city swirling with sand, the institute was in the process of moving its collection into a new, state-of-the-art building. The fighters commandeered the new center, turning it into a dormitory for one of their units of foreign fighters, Cisse said. They didn't realize only about 2,000 manuscripts had been moved there, the bulk of the collection remaining at the old library, he said.

The Islamists came in, as they did in Afghanistan, with their own, severe interpretation of Islam, intent on rooting out what they saw as the veneration of idols instead of the pure worship of Allah. During their 10-month-rule, they eviscerated much of the identity of this storied city, starting with the mausoleums of their saints, which were reduced to rubble.

The turbaned fighters made women hide their faces and blotted out their images on billboards. They closed hair salons, banned makeup and forbade the music for which Mali is known.

Their final act before leaving was to go through the exhibition room in the institute, as well as the whitewashed laboratory used to restore the age-old parchments. They grabbed the books they found and burned them.

However, they didn't bother searching the old building, where an elderly man named Abba Alhadi has spent 40 of his 72 years on earth taking care of rare manuscripts. The illiterate old man, who walks with a cane and looks like a character from the Bible, was the perfect foil for the Islamists. They wrongly assumed that the city's European-educated elite would be the ones trying to save the manuscripts, he said.

So last August, Alhadi began stuffing the thousands of books into empty rice and millet sacks.

At night, he loaded the millet sacks onto the type of trolley used to cart boxes of vegetables to the market. He pushed them across town and piled them into a lorry and onto the backs of motorcycles, which drove them to the banks of the Niger River.

From there, they floated down to the central Malian town of Mopti in a pinasse, a narrow, canoe-like boat. Then cars drove them from Mopti, the first government-controlled town, to Mali's capital, Bamako, over 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) from here.

"I have spent my life protecting these manuscripts. This has been my life's work. And I had to come to terms with the fact that I could no longer protect them here," said Alhadi. "It hurt me deeply to see them go, but I took strength knowing that they were being sent to a safe place."

It took two weeks in all to spirit out the bulk of the collection, around 28,000 texts housed in the old building covering the subjects of theology, astronomy, geography and more.

There was nothing they could do, however, for the 2,000 documents that had already been transferred to the new library, to its exhibition and restoration rooms, and to a basement vault. Cisse took solace knowing that most of the texts in the new library had been digitized.

Even so, when his staff came to tell him about the fire, he felt a constriction in his chest.

The new library is housed inside a modern building, whose sheer walls are made to resemble the mud-walled homes of Timbuktu. Cisse braved his fear to slip through the back gate on the morning of Jan. 24.

The alarm was still screaming. The empty manuscript boxes were strewn on the ground outside in the brick courtyard. All that was left of the books was a soft, feathery ash.

Cisse then entered the library. The glass cases in the exhibit room were empty. So was the manuscript restoration lab, its white tables blanketed in dust. The manuscripts left out were gone.

But the librarian knew the bulk of the books was in a storage room in the basement. With the alarm still screaming, he walked down the flight of pitch-black stairs.

The room had been locked shut. And he was too afraid to open it, because the mayor of Timbuktu had warned residents that the retreating rebels had mined the town and booby-trapped strategic buildings.

So he waited.

On Jan. 28, a column of more than 600 French troops rolled into the city.

The same day, they came to inspect the institute. They spraypainted in pink the word "OK" in front of each room they cleared, working their way to the basement. They pummeled the locked door. When the door slapped open, Cisse felt as if his chest was about to explode.

They beamed a flashlight into the darkness. In the pools of light, he made out the little bundles of parchments sitting on the rafters. They were where they had left them nearly a year ago, in a room the Islamists had never discovered.

The director-general of UNESCO toured the damaged library this weekend, alongside French President Francois Hollande, who made a triumphant visit to Timbuktu. She described the manuscripts as a global treasure. "They are part of our world heritage," said Irina Bokova. "They are important for all of Africa, as well as for all of the world."

Cisse estimates that what was lost in the end is less than 5 percent of the Ahmed Baba collection. Which texts were burned is not yet known.

He stresses that all the manuscripts, which date back over 700 years, are irreplaceable. They are hand-written in a variety of scripts, and include ornate illustrations embedded within the text.

The collection is itself only a portion of the estimated 101,820 manuscripts stored in private libraries here, the product of the confluence of caravan routes which passed through Timbuktu and fostered an extensive trading network, including in books. Among the most valuable are the Tarikh al-Sudan and the Tarikh al-Fattash, chronicles which describe life in Timbuktu during the Songhai empire in the 16th century.

"We lost a lot of our riches. But we were also able to save a great deal of our riches, and for that I am overcome with joy," Cisse said. "These manuscripts represent who we are.... I saved these books in the name of Timbuktu first, because I am from Timbuktu. . Then I did it for my country. And also for all of humanity. Because knowledge is for all of humanity."

___

Rukmini Callimachi can be reached at www.twitter.com/rcallimachi

People of Timbuktu save manuscripts from invaders

— Feb. 4 6:59 PM EST

You are here

Home » Francois Hollande » People of Timbuktu save manuscripts from invaders

By: RUKMINI CALLIMACHI (AP)

TIMBUKTU, MaliCopyright 2013 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.16.7735-3.00742

The al-Qaida-linked extremists who ransacked the institute wanted to deal a final blow to Mali, whose northern half they had held for 10 months before retreating in the face of a French-led military advance. They also wanted to deal a blow to the world, especially France, whose capital houses the headquarters of UNESCO, the organization which recognized and elevated Timbuktu's monuments to its list of World Heritage sites.

So as they left, they torched the Ahmed Baba Institute of Higher Learning and Islamic Research, aiming to destroy a heritage of 30,000 manuscripts that date back to the 13th century.

"These manuscripts are our identity," said Abdoulaye Cisse, the library's acting director. "It's through these manuscripts that we have been able to reconstruct our own history, the history of Africa . People think that our history is only oral, not written. What proves that we had a written history are these documents."

The first people who spotted the column of black smoke on Jan. 23 were the residents whose homes surround the library, and they ran to tell the center's employees. The bookbinders, manuscript restorers and security guards who work for the institute broke down and cried.

Just about the only person who didn't was Cisse, the acting director, who for months had harbored a secret. Starting last year, he and a handful of associates had conspired to save the documents so crucial to this 1,000-year-old town.

In April, when the rebels preaching a radical version of Islam first rolled into this city swirling with sand, the institute was in the process of moving its collection into a new, state-of-the-art building. The fighters commandeered the new center, turning it into a dormitory for one of their units of foreign fighters, Cisse said. They didn't realize only about 2,000 manuscripts had been moved there, the bulk of the collection remaining at the old library, he said.

The Islamists came in, as they did in Afghanistan, with their own, severe interpretation of Islam, intent on rooting out what they saw as the veneration of idols instead of the pure worship of Allah. During their 10-month-rule, they eviscerated much of the identity of this storied city, starting with the mausoleums of their saints, which were reduced to rubble.

The turbaned fighters made women hide their faces and blotted out their images on billboards. They closed hair salons, banned makeup and forbade the music for which Mali is known.

Their final act before leaving was to go through the exhibition room in the institute, as well as the whitewashed laboratory used to restore the age-old parchments. They grabbed the books they found and burned them.

However, they didn't bother searching the old building, where an elderly man named Abba Alhadi has spent 40 of his 72 years on earth taking care of rare manuscripts. The illiterate old man, who walks with a cane and looks like a character from the Bible, was the perfect foil for the Islamists. They wrongly assumed that the city's European-educated elite would be the ones trying to save the manuscripts, he said.

So last August, Alhadi began stuffing the thousands of books into empty rice and millet sacks.

At night, he loaded the millet sacks onto the type of trolley used to cart boxes of vegetables to the market. He pushed them across town and piled them into a lorry and onto the backs of motorcycles, which drove them to the banks of the Niger River.

From there, they floated down to the central Malian town of Mopti in a pinasse, a narrow, canoe-like boat. Then cars drove them from Mopti, the first government-controlled town, to Mali's capital, Bamako, over 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) from here.

"I have spent my life protecting these manuscripts. This has been my life's work. And I had to come to terms with the fact that I could no longer protect them here," said Alhadi. "It hurt me deeply to see them go, but I took strength knowing that they were being sent to a safe place."

It took two weeks in all to spirit out the bulk of the collection, around 28,000 texts housed in the old building covering the subjects of theology, astronomy, geography and more.

There was nothing they could do, however, for the 2,000 documents that had already been transferred to the new library, to its exhibition and restoration rooms, and to a basement vault. Cisse took solace knowing that most of the texts in the new library had been digitized.

Even so, when his staff came to tell him about the fire, he felt a constriction in his chest.

The new library is housed inside a modern building, whose sheer walls are made to resemble the mud-walled homes of Timbuktu. Cisse braved his fear to slip through the back gate on the morning of Jan. 24.

The alarm was still screaming. The empty manuscript boxes were strewn on the ground outside in the brick courtyard. All that was left of the books was a soft, feathery ash.

Cisse then entered the library. The glass cases in the exhibit room were empty. So was the manuscript restoration lab, its white tables blanketed in dust. The manuscripts left out were gone.

But the librarian knew the bulk of the books was in a storage room in the basement. With the alarm still screaming, he walked down the flight of pitch-black stairs.

The room had been locked shut. And he was too afraid to open it, because the mayor of Timbuktu had warned residents that the retreating rebels had mined the town and booby-trapped strategic buildings.

So he waited.

On Jan. 28, a column of more than 600 French troops rolled into the city.

The same day, they came to inspect the institute. They spraypainted in pink the word "OK" in front of each room they cleared, working their way to the basement. They pummeled the locked door. When the door slapped open, Cisse felt as if his chest was about to explode.

They beamed a flashlight into the darkness. In the pools of light, he made out the little bundles of parchments sitting on the rafters. They were where they had left them nearly a year ago, in a room the Islamists had never discovered.

The director-general of UNESCO toured the damaged library this weekend, alongside French President Francois Hollande, who made a triumphant visit to Timbuktu. She described the manuscripts as a global treasure. "They are part of our world heritage," said Irina Bokova. "They are important for all of Africa, as well as for all of the world."

Cisse estimates that what was lost in the end is less than 5 percent of the Ahmed Baba collection. Which texts were burned is not yet known.

He stresses that all the manuscripts, which date back over 700 years, are irreplaceable. They are hand-written in a variety of scripts, and include ornate illustrations embedded within the text.

The collection is itself only a portion of the estimated 101,820 manuscripts stored in private libraries here, the product of the confluence of caravan routes which passed through Timbuktu and fostered an extensive trading network, including in books. Among the most valuable are the Tarikh al-Sudan and the Tarikh al-Fattash, chronicles which describe life in Timbuktu during the Songhai empire in the 16th century.

"We lost a lot of our riches. But we were also able to save a great deal of our riches, and for that I am overcome with joy," Cisse said. "These manuscripts represent who we are.... I saved these books in the name of Timbuktu first, because I am from Timbuktu. . Then I did it for my country. And also for all of humanity. Because knowledge is for all of humanity."

___

Rukmini Callimachi can be reached at www.twitter.com/rcallimachi

Is this the oldest d20 on Earth?

Is this the oldest d20 on Earth?

Romans may have used 20-Sided die almost two millennia before D&D, but people in ancient Egypt were casting icosahedra even earlier. Pictured above is a twenty-faced die dating from somewhere between 304 and 30 B.C., a timespan also known as Egypt's Ptolemaic Period.

Romans may have used 20-Sided die almost two millennia before D&D, but people in ancient Egypt were casting icosahedra even earlier. Pictured above is a twenty-faced die dating from somewhere between 304 and 30 B.C., a timespan also known as Egypt's Ptolemaic Period.

According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the gamepiece is held, the die was once held in the collection of one Reverend Chauncey Murch, who acquired it between 1883 and 1906 while conducting missionary work in Egypt.

Got a 20-sided die that predates the Ptolemaic Period? Post about it in the comments.

[The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

this is awesomedungeons and dragonsarchaeologyd°yptafricad2020 sided dieicosahedronarcheologysciencescigeometrymaths

Is this the oldest d20 on Earth?

Romans may have used 20-Sided die almost two millennia before D&D, but people in ancient Egypt were casting icosahedra even earlier. Pictured above is a twenty-faced die dating from somewhere between 304 and 30 B.C., a timespan also known as Egypt's Ptolemaic Period.

Romans may have used 20-Sided die almost two millennia before D&D, but people in ancient Egypt were casting icosahedra even earlier. Pictured above is a twenty-faced die dating from somewhere between 304 and 30 B.C., a timespan also known as Egypt's Ptolemaic Period.According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the gamepiece is held, the die was once held in the collection of one Reverend Chauncey Murch, who acquired it between 1883 and 1906 while conducting missionary work in Egypt.

Got a 20-sided die that predates the Ptolemaic Period? Post about it in the comments.

[The Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Monday, February 4, 2013

Dismember Orcs With Your Snazzy New $10,000 HOBBIT Sword | Badass Digest

Dismember Orcs With Your Snazzy New $10,000 HOBBIT Sword | Badass Digest

Dismember Orcs With Your Snazzy New $10,000 HOBBIT Sword

Dismember Orcs With Your Snazzy New $10,000 HOBBIT Sword

NOTE: Orcs do not exist, and living humans should never be used as substitutes. Even jerks.

Well, if the movie business ever totally implodes, at least WETA can sit comfortably knowing they can always just go into the novelty sword business, although it's difficult to imagine a scenario short of zombie apocalypse in which movies would be gone but movie swords would still be in demand.

This is WETA's replica of The Hobbit's Orcrist sword, aka "The Goblin Cleaver," aka "Biter." I'm not up on my Tolkien lore, but I believe this is the sword which belongs to Thorin, the main Dwarf in The Hobbit. If that's not specific enough, imagine the two or three dwarves that inexplicably looked like male models, Thorin is the most Gerard Butler one.

It sure looks pretty. I'm not sure exactly what separates this from being a real goddamn sword. It has a scabbard made of real fancy scabbard materials. The killing part is made out of something called "spring steel." I don't know what this is, but I find the idea of "winter steel" far more threatening.

Were you to buy one of these babies, you'd surely be the laughing stock of your neighborhood, until you started using it, I suppose. This could be the most valuable thing in your house and The Wet Bandits would probably pass it up for your iPad. I'll buy mine in a couple years when they get to be Pawn Shop priced.

This is WETA's replica of The Hobbit's Orcrist sword, aka "The Goblin Cleaver," aka "Biter." I'm not up on my Tolkien lore, but I believe this is the sword which belongs to Thorin, the main Dwarf in The Hobbit. If that's not specific enough, imagine the two or three dwarves that inexplicably looked like male models, Thorin is the most Gerard Butler one.

It sure looks pretty. I'm not sure exactly what separates this from being a real goddamn sword. It has a scabbard made of real fancy scabbard materials. The killing part is made out of something called "spring steel." I don't know what this is, but I find the idea of "winter steel" far more threatening.

Were you to buy one of these babies, you'd surely be the laughing stock of your neighborhood, until you started using it, I suppose. This could be the most valuable thing in your house and The Wet Bandits would probably pass it up for your iPad. I'll buy mine in a couple years when they get to be Pawn Shop priced.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)