Richard III: DNA confirms twisted bones belong to king

Skeleton found beneath Leicester car park confirmed as that of Richard III, as work begins on new tomb near excavation site

• Read the latest on the discovery here

• Read the latest on the discovery here

Not just the identity of the man in the car park with the twisted spine, but the appalling last moments and humiliating treatment of the naked body of Richard III in the hours after his death have been revealed at an extraordinary press conference at Leicester University.

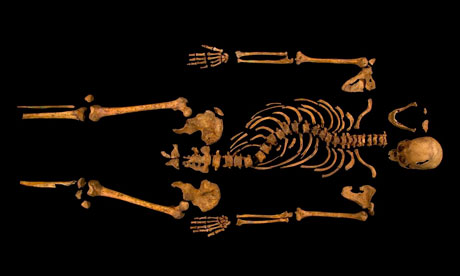

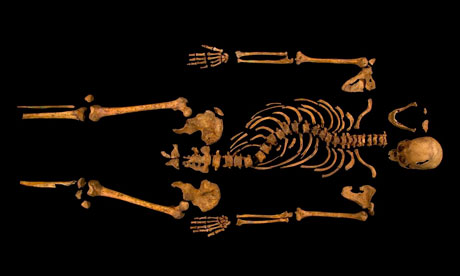

There were cheers when Richard Buckley, lead archaeologist on the hunt for the king's body, finally announced that the university team was convinced "beyond reasonable doubt" that it had found the last Plantagenet king, bent by scoliosis of the spine, and twisted further to fit into a hastily dug hole in Grey Friars church, which was slightly too small to hold his body.

Grey Friars car park, Leicester, where the remains of King Richard III were found. Photograph: Darren Staples/Reuters But by then it was clear the evidence was overwhelming, as the scientists who carried out the DNA tests, those who created the computer-imaging technology to peer on to and into the bones in raking detail, the genealogists who found a distant descendant with matching DNA, and the academics who scoured contemporary texts for accounts of the king's death and burial, outlined their findings.

Grey Friars car park, Leicester, where the remains of King Richard III were found. Photograph: Darren Staples/Reuters But by then it was clear the evidence was overwhelming, as the scientists who carried out the DNA tests, those who created the computer-imaging technology to peer on to and into the bones in raking detail, the genealogists who found a distant descendant with matching DNA, and the academics who scoured contemporary texts for accounts of the king's death and burial, outlined their findings.

"What a morning. What a story," said Philippa Langley, of the Richard III Society. She had been driving on the project for years, in the face of incredulity from many people, and finding funds from Ricardians all over the world when it looked as if the money would run out before the excavation had even begun.

Canadian-born Michael Ibsen, a direct descendant of Richard III's eldest sister, Anne of York, uses an oral swab to give a DNA sample to researchers. Photograph: Colin Brooks/AFP/Getty Images Work has started on designing a new tomb in the cathedral, only 100 yards from the excavation site, and Canon David Monteith said a solemn multifaith ceremony would be held to lay him into his new grave there, probably next year. Leicester's museums service is working on plans for a new visitor centre in an old school building overlooking the site.

Canadian-born Michael Ibsen, a direct descendant of Richard III's eldest sister, Anne of York, uses an oral swab to give a DNA sample to researchers. Photograph: Colin Brooks/AFP/Getty Images Work has started on designing a new tomb in the cathedral, only 100 yards from the excavation site, and Canon David Monteith said a solemn multifaith ceremony would be held to lay him into his new grave there, probably next year. Leicester's museums service is working on plans for a new visitor centre in an old school building overlooking the site.

Richard died at Bosworth on 22 August 1485, the last English king to fall in battle, and the researchers revealed how for the first time. There was an audible intake of breath as a slide came up showing the base of his skull sliced off by one terrible blow, believed to be from a halberd, a fearsome medieval battle weapon with a razor-sharp iron axe blade weighing about two kilos, mounted on a wooden pole, which was swung at Richard at very close range. The blade probably penetrated several centimetres into his brain and, said the human bones expert Jo Appleby, he would have been unconscious at once and dead almost as soon.

The skull of Richard III. Injuries to the skeleton appear to confirm contemporary accounts that the king died in battle. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images The injury appears to confirm contemporary accounts that he died in close combat in the thick of the battle and unhorsed – as in the great despairing cry Shakespeare gives him: "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!"

The skull of Richard III. Injuries to the skeleton appear to confirm contemporary accounts that the king died in battle. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images The injury appears to confirm contemporary accounts that he died in close combat in the thick of the battle and unhorsed – as in the great despairing cry Shakespeare gives him: "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!"

Another sword slash, which also went through the bone and into the brain, would also have proved fatal. But many of the other injuries were after death, suggesting a gruesome ritual on the battlefield and as the king's body was brought back to Leicester, as he was stripped, mocked and mutilated – which would have revealed for the first time to any but his closest intimates the twisted back, a condition from an unknown cause, which began to contort his body from the age of about 10. By the time he died he would have stood inches shorter than his true height of 5' 8", tall for a medieval man. The bones were those of an unusually slight, delicately built man – Appleby described him as having an "almost feminine" build – which also matches contemporary descriptions.

Jo Appleby, a lecturer in human bioarchaeology at the University of Leicester, who led the exhumation, is hugged by Prof Lin Foxhall. Photograph: Rui Vieira/PA One terrible injury, a stab through the right buttock and into his pelvis, was certainly after death, and could not have happened when his lower body was protected by armour. It suggests the story that his naked corpse was brought back slung over the pommel of a horse, mocked and abused all the way, was true. Bob Savage, a medieval arms expert from the Royal Armouries who helped identify the wounds, said it was probably not a war weapon, but the sort of sharp knife or dagger any workman might have carried.

Jo Appleby, a lecturer in human bioarchaeology at the University of Leicester, who led the exhumation, is hugged by Prof Lin Foxhall. Photograph: Rui Vieira/PA One terrible injury, a stab through the right buttock and into his pelvis, was certainly after death, and could not have happened when his lower body was protected by armour. It suggests the story that his naked corpse was brought back slung over the pommel of a horse, mocked and abused all the way, was true. Bob Savage, a medieval arms expert from the Royal Armouries who helped identify the wounds, said it was probably not a war weapon, but the sort of sharp knife or dagger any workman might have carried.

Michael Ibsen, the Canadian-born furniture maker proved as the descendant of Richard's sister, heard the confirmation on Sunday and listened to the unfolding evidence in shocked silence. "My head is no clearer now than when I first heard the news," he said. "Many, many hundreds of people died on that field that day. He was a king, but just one of the dead. He lived in very violent times, and these deaths would not have been pretty or quick."

It was Mathew Morris who first uncovered the body, in the first hour of the first day of the excavation. He did not believe he had found the king. The mechanical digger was still chewing the tarmac off the council car park, identified by years of research by local historians and the Richard III Society as the probable site of the lost church of Grey Friars, whose priests bravely claimed the body of the king and buried him in a hastily dug grave, probably still naked, but in a position of honour near the high altar of their church. The leg bones just showing through the soil were covered up again.

Sir Laurence Olivier as Richard III. The actor also directed the 1955 film. Photograph: The Criterion Collection/Sportsphoto/Allstar Ten days later, on 5 September, when further excavation proved Morris had hit the crucial spot at the edge of the choir in the church, he returned with Lin Foxhall, head of the archaeology department, and Appleby, swathed in crime scene overalls to prevent contamination, to excavate the body. "We did it the usual way, lifting the arms, legs and skull first, and proceeding gradually towards the torso – so it was only when we finally saw the twisted spine that I thought: 'My word, I think we've got him.'"

Sir Laurence Olivier as Richard III. The actor also directed the 1955 film. Photograph: The Criterion Collection/Sportsphoto/Allstar Ten days later, on 5 September, when further excavation proved Morris had hit the crucial spot at the edge of the choir in the church, he returned with Lin Foxhall, head of the archaeology department, and Appleby, swathed in crime scene overalls to prevent contamination, to excavate the body. "We did it the usual way, lifting the arms, legs and skull first, and proceeding gradually towards the torso – so it was only when we finally saw the twisted spine that I thought: 'My word, I think we've got him.'"

Turi King, leader of the DNA team, said she completed her work confirming the mitochondrial DNA match only on Saturday night, and there is more work to be done on the Y chromosome through the male line.

The complete skeleton showing the curved spine of Richard III, who was killed in the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Photograph: EPA As far as Langley is concerned, Richard was the true king, the last king of the north, a worthy and brave leader who became a victim of some of the most brilliant propaganda in history, in the hands of the Tudors' image-maker, Shakespeare.

The complete skeleton showing the curved spine of Richard III, who was killed in the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Photograph: EPA As far as Langley is concerned, Richard was the true king, the last king of the north, a worthy and brave leader who became a victim of some of the most brilliant propaganda in history, in the hands of the Tudors' image-maker, Shakespeare.

Foxhall quoted one contemporary description of Richard as "slight in body and weak in strength … to his last breath he held himself nobly in a defending manner".

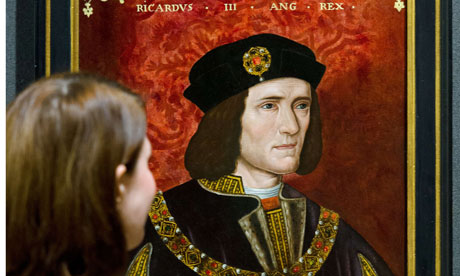

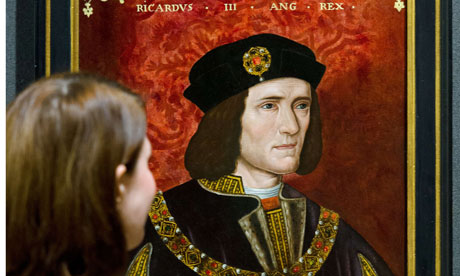

A painting of King Richard III by an unknown artist is displayed in the National Portrait Gallery in central London. Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images There remains the dark shadow of the little princes in the tower, an infamous story even in Richard's day: the child Edward V and his brother Richard, declared illegitimate when Richard III claimed the throne, imprisoned in the Tower of London and never seen alive again. King said that although it is by no means certain that the bones claimed found at the tower centuries later were theirs, there may be more DNA detective work to be done there.

A painting of King Richard III by an unknown artist is displayed in the National Portrait Gallery in central London. Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images There remains the dark shadow of the little princes in the tower, an infamous story even in Richard's day: the child Edward V and his brother Richard, declared illegitimate when Richard III claimed the throne, imprisoned in the Tower of London and never seen alive again. King said that although it is by no means certain that the bones claimed found at the tower centuries later were theirs, there may be more DNA detective work to be done there.

"I'm a medievalist really," Morris said. "I don't go much for the Tudors. Even if Richard did kill the princes in the tower, you have to judge him by the standards of his day – no other medieval king would have taken the risk of leaving them alive."

There were cheers when Richard Buckley, lead archaeologist on the hunt for the king's body, finally announced that the university team was convinced "beyond reasonable doubt" that it had found the last Plantagenet king, bent by scoliosis of the spine, and twisted further to fit into a hastily dug hole in Grey Friars church, which was slightly too small to hold his body.

Grey Friars car park, Leicester, where the remains of King Richard III were found. Photograph: Darren Staples/Reuters But by then it was clear the evidence was overwhelming, as the scientists who carried out the DNA tests, those who created the computer-imaging technology to peer on to and into the bones in raking detail, the genealogists who found a distant descendant with matching DNA, and the academics who scoured contemporary texts for accounts of the king's death and burial, outlined their findings.

Grey Friars car park, Leicester, where the remains of King Richard III were found. Photograph: Darren Staples/Reuters But by then it was clear the evidence was overwhelming, as the scientists who carried out the DNA tests, those who created the computer-imaging technology to peer on to and into the bones in raking detail, the genealogists who found a distant descendant with matching DNA, and the academics who scoured contemporary texts for accounts of the king's death and burial, outlined their findings."What a morning. What a story," said Philippa Langley, of the Richard III Society. She had been driving on the project for years, in the face of incredulity from many people, and finding funds from Ricardians all over the world when it looked as if the money would run out before the excavation had even begun.

Canadian-born Michael Ibsen, a direct descendant of Richard III's eldest sister, Anne of York, uses an oral swab to give a DNA sample to researchers. Photograph: Colin Brooks/AFP/Getty Images Work has started on designing a new tomb in the cathedral, only 100 yards from the excavation site, and Canon David Monteith said a solemn multifaith ceremony would be held to lay him into his new grave there, probably next year. Leicester's museums service is working on plans for a new visitor centre in an old school building overlooking the site.

Canadian-born Michael Ibsen, a direct descendant of Richard III's eldest sister, Anne of York, uses an oral swab to give a DNA sample to researchers. Photograph: Colin Brooks/AFP/Getty Images Work has started on designing a new tomb in the cathedral, only 100 yards from the excavation site, and Canon David Monteith said a solemn multifaith ceremony would be held to lay him into his new grave there, probably next year. Leicester's museums service is working on plans for a new visitor centre in an old school building overlooking the site.Richard died at Bosworth on 22 August 1485, the last English king to fall in battle, and the researchers revealed how for the first time. There was an audible intake of breath as a slide came up showing the base of his skull sliced off by one terrible blow, believed to be from a halberd, a fearsome medieval battle weapon with a razor-sharp iron axe blade weighing about two kilos, mounted on a wooden pole, which was swung at Richard at very close range. The blade probably penetrated several centimetres into his brain and, said the human bones expert Jo Appleby, he would have been unconscious at once and dead almost as soon.

The skull of Richard III. Injuries to the skeleton appear to confirm contemporary accounts that the king died in battle. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images The injury appears to confirm contemporary accounts that he died in close combat in the thick of the battle and unhorsed – as in the great despairing cry Shakespeare gives him: "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!"

The skull of Richard III. Injuries to the skeleton appear to confirm contemporary accounts that the king died in battle. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images The injury appears to confirm contemporary accounts that he died in close combat in the thick of the battle and unhorsed – as in the great despairing cry Shakespeare gives him: "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!"Another sword slash, which also went through the bone and into the brain, would also have proved fatal. But many of the other injuries were after death, suggesting a gruesome ritual on the battlefield and as the king's body was brought back to Leicester, as he was stripped, mocked and mutilated – which would have revealed for the first time to any but his closest intimates the twisted back, a condition from an unknown cause, which began to contort his body from the age of about 10. By the time he died he would have stood inches shorter than his true height of 5' 8", tall for a medieval man. The bones were those of an unusually slight, delicately built man – Appleby described him as having an "almost feminine" build – which also matches contemporary descriptions.

Jo Appleby, a lecturer in human bioarchaeology at the University of Leicester, who led the exhumation, is hugged by Prof Lin Foxhall. Photograph: Rui Vieira/PA One terrible injury, a stab through the right buttock and into his pelvis, was certainly after death, and could not have happened when his lower body was protected by armour. It suggests the story that his naked corpse was brought back slung over the pommel of a horse, mocked and abused all the way, was true. Bob Savage, a medieval arms expert from the Royal Armouries who helped identify the wounds, said it was probably not a war weapon, but the sort of sharp knife or dagger any workman might have carried.

Jo Appleby, a lecturer in human bioarchaeology at the University of Leicester, who led the exhumation, is hugged by Prof Lin Foxhall. Photograph: Rui Vieira/PA One terrible injury, a stab through the right buttock and into his pelvis, was certainly after death, and could not have happened when his lower body was protected by armour. It suggests the story that his naked corpse was brought back slung over the pommel of a horse, mocked and abused all the way, was true. Bob Savage, a medieval arms expert from the Royal Armouries who helped identify the wounds, said it was probably not a war weapon, but the sort of sharp knife or dagger any workman might have carried.Michael Ibsen, the Canadian-born furniture maker proved as the descendant of Richard's sister, heard the confirmation on Sunday and listened to the unfolding evidence in shocked silence. "My head is no clearer now than when I first heard the news," he said. "Many, many hundreds of people died on that field that day. He was a king, but just one of the dead. He lived in very violent times, and these deaths would not have been pretty or quick."

It was Mathew Morris who first uncovered the body, in the first hour of the first day of the excavation. He did not believe he had found the king. The mechanical digger was still chewing the tarmac off the council car park, identified by years of research by local historians and the Richard III Society as the probable site of the lost church of Grey Friars, whose priests bravely claimed the body of the king and buried him in a hastily dug grave, probably still naked, but in a position of honour near the high altar of their church. The leg bones just showing through the soil were covered up again.

Sir Laurence Olivier as Richard III. The actor also directed the 1955 film. Photograph: The Criterion Collection/Sportsphoto/Allstar Ten days later, on 5 September, when further excavation proved Morris had hit the crucial spot at the edge of the choir in the church, he returned with Lin Foxhall, head of the archaeology department, and Appleby, swathed in crime scene overalls to prevent contamination, to excavate the body. "We did it the usual way, lifting the arms, legs and skull first, and proceeding gradually towards the torso – so it was only when we finally saw the twisted spine that I thought: 'My word, I think we've got him.'"

Sir Laurence Olivier as Richard III. The actor also directed the 1955 film. Photograph: The Criterion Collection/Sportsphoto/Allstar Ten days later, on 5 September, when further excavation proved Morris had hit the crucial spot at the edge of the choir in the church, he returned with Lin Foxhall, head of the archaeology department, and Appleby, swathed in crime scene overalls to prevent contamination, to excavate the body. "We did it the usual way, lifting the arms, legs and skull first, and proceeding gradually towards the torso – so it was only when we finally saw the twisted spine that I thought: 'My word, I think we've got him.'"Turi King, leader of the DNA team, said she completed her work confirming the mitochondrial DNA match only on Saturday night, and there is more work to be done on the Y chromosome through the male line.

The complete skeleton showing the curved spine of Richard III, who was killed in the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Photograph: EPA As far as Langley is concerned, Richard was the true king, the last king of the north, a worthy and brave leader who became a victim of some of the most brilliant propaganda in history, in the hands of the Tudors' image-maker, Shakespeare.

The complete skeleton showing the curved spine of Richard III, who was killed in the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Photograph: EPA As far as Langley is concerned, Richard was the true king, the last king of the north, a worthy and brave leader who became a victim of some of the most brilliant propaganda in history, in the hands of the Tudors' image-maker, Shakespeare.Foxhall quoted one contemporary description of Richard as "slight in body and weak in strength … to his last breath he held himself nobly in a defending manner".

A painting of King Richard III by an unknown artist is displayed in the National Portrait Gallery in central London. Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images There remains the dark shadow of the little princes in the tower, an infamous story even in Richard's day: the child Edward V and his brother Richard, declared illegitimate when Richard III claimed the throne, imprisoned in the Tower of London and never seen alive again. King said that although it is by no means certain that the bones claimed found at the tower centuries later were theirs, there may be more DNA detective work to be done there.

A painting of King Richard III by an unknown artist is displayed in the National Portrait Gallery in central London. Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images There remains the dark shadow of the little princes in the tower, an infamous story even in Richard's day: the child Edward V and his brother Richard, declared illegitimate when Richard III claimed the throne, imprisoned in the Tower of London and never seen alive again. King said that although it is by no means certain that the bones claimed found at the tower centuries later were theirs, there may be more DNA detective work to be done there."I'm a medievalist really," Morris said. "I don't go much for the Tudors. Even if Richard did kill the princes in the tower, you have to judge him by the standards of his day – no other medieval king would have taken the risk of leaving them alive."